25 May 2022

When we hear the word tabloid, our minds immediately go to exploitative journalism of the lowest kind. But the word got its start in the pharmaceutical industry in the late nineteenth century.

Tabloid, with a capital < T >, was coined as a trademark in 1884 by Burroughs, Wellcome, & Company. It was the company’s name for a pill made of compressed medication and filler, a proprietary name for what was, and still is, otherwise known as a tablet. The tabl- in tabloid is taken from tablet—itself a borrowing from French that could mean a small ornament as well as a writing or painting surface—and the -oid suffix refers to something resembling or akin to the root’s meaning. So, a tabloid is literally something akin to a tablet.

But it did not take long for tabloid, with a lower-case < t >, to become genericized. On 4 July 1885 the medical journal the Lancet published a letter by a physician by the name of John Watson on the efficacy of cocaine in the treatment of hay fever:

I am desirous, with your permission, of calling attention to the value of tabloids of cocaine in the treatment of hay fever.

The letter and references to it were published in numerous journals and newspapers on both sides of the Atlantic. This one is from the 1886 Transactions of the Medical Society of New Jersey:

The profession of Camden are prompt to give new remedies a trial and place them at the proper worth. They express a satisfactory experience with tabloids of cocaine in hay fever and in surgical operations.

Given the news story’s popularity, it almost certainly came to the notice of Arthur Conan Doyle, himself a physician, who would go on to invent the fictional adventures of Sherlock Holmes and Dr. John Watson. One cannot but help to wonder if the association of the name John Watson with cocaine formed part of the inspiration for the literary characters, Holmes being a user of the drug. Conan Doyle would write the first Sherlock Holmes story the following year (1887), and Holmes’s use of cocaine first appears in the 1887 The Sign of the Four. Of course, any such association could be mere coincidence.

And metaphorical use of tabloid quickly followed, referring to anything that was compressed or easily digestible, especially published material. The following description of a reference book appeared in the 24 January 1891 issue of the Pall Mall Gazette:

Another sixpenny marvel is “Kendal and Dent's Edition of Everybody's Pocket Cyclopædia.” It is slim, and daintily bound in cloth—a sort of tabloid of “useful knowledge.”

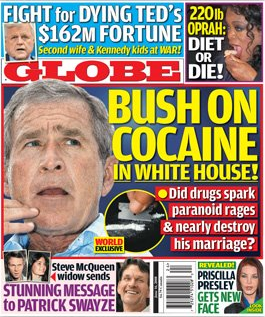

Tabloid entered the world of journalism that same year as a reference to newspapers printed on smaller pieces of paper, folded like a book. In large part because they are easier to handle on public transport, tabloid publications became a popular alternative to the more traditional broadsheet newspapers, but from the very beginning, tabloid papers were associated with low, gossipy journalism.

The following description of Alfred Harmsworth appeared in the March 1891 issue of The Forum. Harmsworth was a British newspaper publisher and a pioneer of tabloid journalism. His first paper was Answers to Correspondents (later shortened to just Answers), but he followed that paper’s success with many others:

One of the phenomena of the nineteenth century—one wonders if the same thing will continue during the present—was the fecundity created by a demand. When a demand existed and an attempt was made to satisfy it, instead of the public being satiated, a new appetite was born. In nothing has this been so marked as in cheap literature, including in the term newspapers and magazines as well as books. The circulation of newspapers and magazines has enormously increased since their reduction in price. One “Answers” could not supply the ever-increasing demand. Mr. Harmsworth's rivals, who were without his creative force, but intelligent enough to follow where he led, saw their opportunity and threw into the insatiable maw “Answers” under other names.

Nor did Mr. Harmsworth propose to suffer the fate of most pioneers and, after having cleared the ground, see others garner the crops. He duplicated and reduplicated his original production, the prototype of the whole family, until to-day the news stands of London are covered with “Answers,” “Tit-Bits,” “Smith's Scraps,” “Jones' Sayings,” “Brown's Hash,” and so on through a couple of score more until one wonders who reads them and how they manage to exist. But the question who reads them is quickly answered. Go into any bus or train or lunch room at any hour of the day or night and you see men and boys and women and girls taking and enjoying their tabloids.

The curious thing is that the reading is no longer confined to the class for whom it was originally intended, as the people of greater intelligence are not ashamed to acknowledge that they are addicted to tabloidism. Last summer, while going from London to Glasgow, I fell in with a middle-aged Englishman, whom I later learned was the executive of a large corporation. He had a bundle of papers and magazines, among them half a dozen brands of tabloids. We engaged in conversation, and he courteously handed me a tabloid. When I expressed a preference for nutriment in another form, he explained that he found in tabloids a mental diversion. “I get tired of ‘The Saturday Review’ and ‘The Spectator,’” he said, “and I read these things because they keep me from thinking.”

Harmsworth would later become the 1st Viscount Northcliffe, proof that no bad deed goes unrewarded, so long as it makes a lot of money.

Sources:

Low, A. Maurice. “’Tabloid Journalism’: Its Causes and Effects.” The Forum (New York), March 1891, 57–58. HathiTrust Digital Archive.

Oxford English Dictionary, third edition, December 2008, s.v. tabloid, n. and adj.

“Reference Books for 1891.” Pall Mall Gazette (London), 24 January 1891, 7. Gale Primary Sources: British Library Newspapers.

“Report of the Standing Committee.” Transactions of the Medical Society of New Jersey, 1886, 129. Nineteenth Century Collections Online.

Watson, John. “Cocaine in the Treatment of Hay Fever” (letter). The Lancet, 4 July 1885, 50. HathiTrust Digital Archive.

Image credit: The Globe, 2009. Fair use of a low-resolution scan of copyrighted material to illustrate the topic under discussion.