13 December 2023

The name Santa Claus is a dialectal variation on the Dutch Sint Klaas. The Sint, or Sante in the Dutch dialect of early New York, obviously corresponds to the English Saint, and the Klaas is somewhat less obviously a hypocoristic form of Nicholas. While in English we typically abbreviate the name as Nick, in Dutch and German it is the final element that is used, resulting in Klaas or Klaus. So Santa Claus is Saint Nicholas.

Almost nothing is known about the historical Saint Nicholas, and it is even possible that he never actually existed. The only thing about him that is known with any degree of confidence is that he was (probably) a fourth-century bishop of Myra, in Asia Minor. Everything else that is “known” about him can be relegated to the status of myth. The most famous story about him, and the one that associates him with gift-giving, is his supposed gift of dowries to three poor, young women in order to keep them from being forced into prostitution. But this, like all of the other stories about him, is a later folkloric addition and was originally ascribed to earlier, pagan mythical figures, only later transferred onto the saint. Saint Nicholas’s feast day is 6 December, hence his association with Yuletide festivities.

Santa Claus is originally a distinctly Americanized and secularized incarnation of the saint. The name arose in colonial New York, a region steeped in Dutch tradition—New York was originally New Amsterdam and ceded to the British and renamed in 1664. The first citation of the name Santa Claus that I’m aware of is from the 20 December 1773 edition of the New York Gazette and Weekly Mercury:

Last Monday the Anniversary of St. Nicholas, otherwise called St. A Claus, was celebrated at Protestant Hall, at Mr. Waldron’s, where a great number of the Sons of that ancient Saint celebrated the Day with great Joy and Festivity.

And we see the form Santaclaus in Washington Irving’s Salmagundi of 25 January 1808:

In his days, according to my grandfather, were first in vented those notable cakes, hight new-year cookies, which originally were impressed on one side with the honest burley countenance of the illustrious Rip, and on the other with that of the noted St. Nicholas, vulgarly called Santaclaus—of all the saints in the kalendar the most venerated by true hollanders, and their unsophisticated descendants. These cakes are to this time given on the first of January, to all visitors, together with a glass of cherry-bounce, or raspberry-brandy.

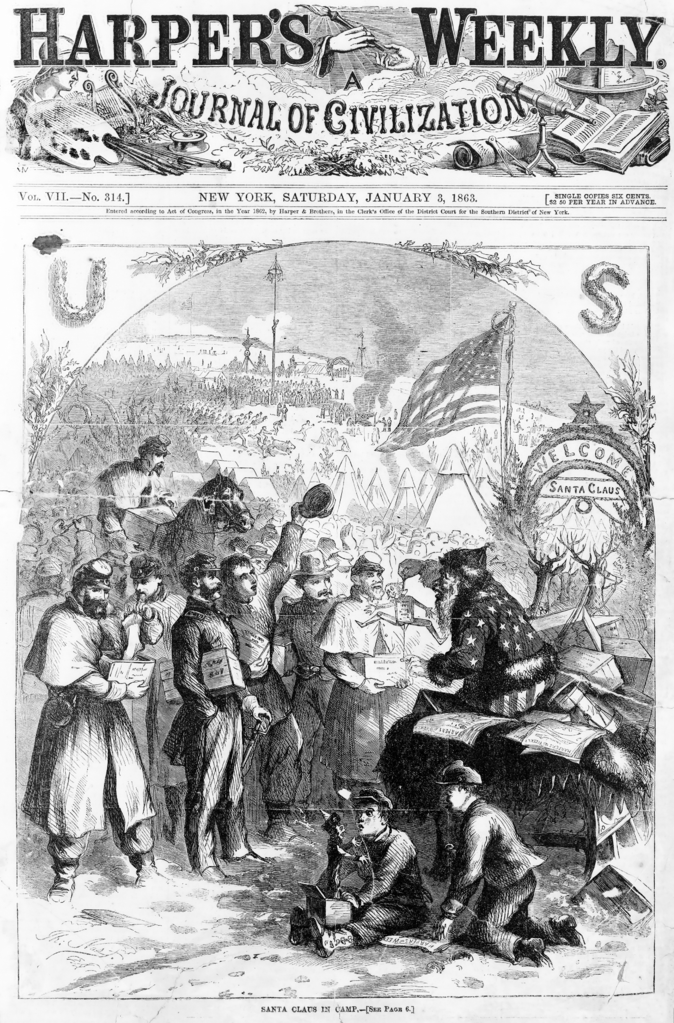

The 1823 poem A Visit from St. Nicholas by Clement C. Moore, another New Yorker, although it does not use the name Santa Claus, created much of the modern lore about the character, including his fur clothing, being fat with a “little round belly,” and his sleigh with “eight tiny reindeer.” But there are differences, notably in that the St. Nicholas of the poem was tiny and elfin. In 1863 cartoonist Thomas Nast depicted Santa Claus in much the way we see him today for the cover of Harper’s magazine. The cover shows Santa visiting Union troops during the US Civil War. In 1881, Nast would depict a more refined image of Santa, seen above, again in the pages of Harper’s.

Like many other aspects of American culture, Santa Claus has been exported and has supplanted or co-exists with other conceptions of St. Nicholas and Christmas gift-givers around the world.

Sources:

Irving, Washington (pseud. Launcelot Langstaff). “From My Elbow-Chair.” Salmagundi, 2.10, 25 January 1808, 407–08. HathiTrust Digital Archive.

“New-York, December 20.” New-York Gazette and the Weekly Mercury, 20 December 1773, 3/1. Readex: America’s Historical Newspapers.

Oxford English Dictionary, second edition, 1989, s.v. Santa Claus, n.

Image credits: Thomas Nast, “Merry Old Santa Claus,” Harper’s Weekly, 1 January 1881, Wikimedia Commons; Thomas Nast, “Santa Claus in Camp,” Harper’s Weekly, 3 January 1863, Wikimedia Commons. Both images are in the public domain.