6 October 2021

Sabotage, as one might guess from the word’s ending, is a borrowing from French, and that borrowing occurred in the opening years of the twentieth century. The root, sabot, literally means a wooden shoe or clog. The route from shoe to malicious damage is not clear on its face and has spawned at least one myth regarding the origin of the latter meaning, but when one looks at the use of the word in French, how it came to mean malicious damage becomes clear.

In addition to the sense of a shoe, the French word became associated with shoddy workmanship, with bungling on the job. Here’s a series of entries from a 1906 French-English dictionary:

sabot sa´bo m. sabot, wooden shoe; horse’s hoof; clog, turban-shell; socket (of furniture); child’s top; wretched fiddle; (of ships) old tub; dormir comme un sabot, sleep like a top.

sabotage sabɔ´ta:ʒ m. manufacture of wooden shoes.

saboter sabɔ´te intr. spin a top; clatter with one’s shoes; turn out poor work. — tr. bungle, make a botch of.

saboteur sabɔ´tə:r m. bungler.

The association with bungling comes from the fact that sabots were primarily worn by agricultural workers and may stem from the idea that when such workers came to the city and manufacturing jobs, they were unskilled and tended to produce shoddy products. Alternatively, it could come from the more straightforward, but still stereotypical, association with rural yokels being foolish and inept.

In the hands of the burgeoning labor movement of the era, however, sabotage, meaning a bungled job, took on a more deliberate connotation. Workers would deliberately bungle as form of labor protest. The word first appears in English in this sense in labor and socialist publications. The following, which appears in the Daily People of 15 July 1906, describes the tactics of the French labor unionists:

No useless riots in the streets; the old romantic Blanquist tactics are forgotten, but the use of what they name “action direct” (direct action), which I will try to describe as follows:

First—In case of strike—use violent picketing, knock down scabs, and go as far as burning down the shop. (In Fresseneville they burnt down the shop and the house of the boass, who had a narrow escape in an automobile). If the scabs, when going to work, are protected by soldiers, they did not bother about picketing, and went to the houses of the scabs and “saw” them there.

Second—In case of work—use “sabotage”: I try to translate that word as “go-canny.” For instance, bakery workers threatened to put ovens out of use by pouring petroleum on the dead-plate. This (does not poison the bread, but it makes bread ill-smelling). Ways of using “sabotage” are countless: when properly used, they will be terrible and deadly weapons.

There are two things of note here. First, the word has not yet been Anglicized; it appears in quotation marks, a definition is given, and it is being used in the context of France. Second, sabotage is not being used in the current sense of malicious damage—that would be the actions described in the first case. Rather, it is being used in the sense of sly and inventive means to produce shoddy products.

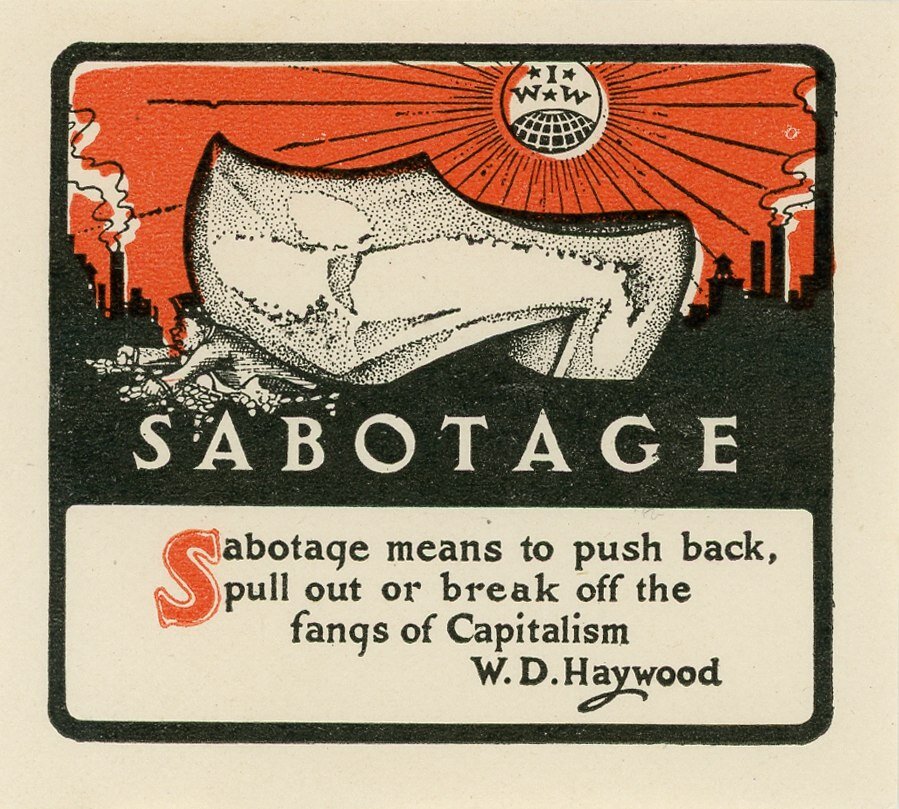

But within a few years sabotage would become fully Anglicized and integrated into English. The Coal Trade Bulletin of September 1914, for example, uses both sabotage and direct action, seen and defined in the above quotation, as English words without need of explanation. The WF of M is the Western Federation of Miners, and the IWW is the Industrial Workers of the World, a.k.a. the Wobblies, a more radical, general union that favored direct action:

All because a large number of misguided dupes listened and were led astray by the ideas of a few impossibilists who wanted nothing else than the opportunity of ruling the W.F. of M. and then turning them over to that aggregation of self-appointed labor saviors who preach direct action (except where it’s on syndicalism), sabotage, etc., the I.W.W.

And the verb to sabotage is recorded a few years later. Here it is in an article from the Nottingham Evening Post of 15 August 1918 about the impending collapse of Germany in the closing days of WWI. It is also being used in a more general, metaphorical sense, rather than the specific sense of destruction of property:

The newspaper mentioned [i.e., the National Zeitung (Berne)] understands that the German disaster has unpleasantly surprised official Austrian circles and caused consternation among the population. “The Austrian social organisation is bankrupt, and the war is being sabotaged,” adds this newspaper.

The aforementioned myth is that sabotage comes from protesting workers throwing their wooden shoes into machinery, thereby damaging the equipment and halting production. The myth is an old one, but got a boost in 1991 when it was repeated in the movie Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country. But tossing shoes in the gears, as we have seen, is not the phrase’s origin. The actual origin, at least in my opinion, is one of the many cases where the real origin is more interesting than the mythical one.

Sources:

“The Coming Collapse of Germany.” Nottingham Evening Post (England), 15 August 1918, 1. Gale Primary Sources: British Library Newspapers.

Bruckere, A. “The French Labor Movement.” Daily People (New York), 15 July 1906, 4. Readex: America’s Historic Newspapers.

International French-English and English-French Dictionary. New York: Hinds, Hayden and Eldridge, 1906, 541. HathiTrust Digital Archive.

Online Etymology Dictionary, 2021, s.v. sabotage, n.

Oxford English Dictionary, second edition, 1989, s.v. sabotage, n., sabot, n.

“United Mine Workers’ Delegates Report on Convention of Western Federation of Miners.” Coal Trade Bulletin, 31.7, 1 September 1914, 24. Gale Primary Sources: Archives Unbound.

Image credit: Unknown artist. Industrial Workers of the World (I.W.W.), 1915. Public domain image.