10 September 2021

Punter is a British slang term for a non-professional gambler, a con man’s mark or victim, a customer of a not-quite-legitimate business, or a prostitute’s client (i.e., a john), with the connotation of a person who can be taken advantage of. The origin is uncertain, but the gambling sense is clearly the original one. The Oxford English Dictionary says punter is probably from a combination of the French ponte and ponter and the Spanish punto, both terms from various card games, but the chronology argues against this, as punter is attested nearly a century before the French or Spanish terms make their way into English.

The earliest attestation of punter that I can find is from 1571, in a list of qualities for which a priest that will be investigated during an inspection by the bishop of London:

Whether your Person, Vicar, or curate, doth openly or secretly, teach or maintaine any erronious or superstitious doctrine. And whether he doe keepe anye suspected woman in his house, or be an inconuenient person, giuen to dronkennesse, or ydlenesse, or be a haunter of Tauernes, Alehouses, or suspected places, a Punter, Banker, Dicer, Carder, Tabler, Swearer, or otherwise give any euill example of life.

[Caveat: the electronic scan of this work in EEBO is not good. The word in question appears to be punter, but an examination of an actual copy of the book, or a better scan, is required to verify that it is indeed punter.]

In contrast, the French and Spanish terms don’t start appearing until the latter half of the seventeenth century. It may be that ponte and punto made their way to England much earlier than we have evidence for, or that these imports reinforced the already existing term.

We see the Spanish punto in a 1660 description of the game of ombre:

By this you see first that the Spadillio, or Ace of Spades is alwayes the first Card, and always Trump, be the Trump what suit soever; and the Basto, or Ace of Clubs always the third. Secondly, that of Black, there are but eleven Trumps, & of Red twelve. Thirdly, that the red Ace enters in the fourth place when it is trump, and then is called the Punto, otherwise ’tis onely rankt after the Knave, and is onely call’d the Ace.

And by the end of the seventeenth century, a punt is being used to mean a gambler who bets against the bank in baccarat, faro, or basset. From Thomas D’Urfey’s 1698 play The Campaigners:

Because I had a little ill luck last night, which was look’d upon as a Miracle too by all the Bassett-Table, the most skilful of all the Punts bless’d himself to see’t; for during the time of play, I had once from an Alpiew or Paroli, Sept et la va, Quinze et le va, Trent en le va: Nay, once Soissant et le va, and yet lost all at last, but ’twas a thousand to one, my Dear.

And a few years later, D’Urfey uses punt again in his 1704 poem Hell Beyond Hell: or the Devil and Mademoiselle:

Then when the Gaming-Night came on,

As Gorgeous as the Mid-day Sun

Th’ Assembly meets, and on the Board,

Scatters like Jove, the dazzling Hoard;

Salutes the *Punts with Bows and Dops,

’Midst Rolls of Fifty, thick as Hops;

And lastly, deals with such Success,

Managing Paroli and Fasse

So well, she all their Purses dreins,

And scarce can count her bulky Gains.

The note for punts reads “a term for Basset-Players,” indicating that D’Urfey did not assume his readers would know this term.

And the verb to punt, meaning to bet against the bank in one of those card games is in place soon after. From a fictional and facetious journal published in Joseph Addison’s Spectator on 11 March 1712:

WEDNESDAY. [...] From Six to Eleven. At Basset. Mem. Never set again upon the Ace of Diamonds.

THURSDAY. From Eleven at Night to Eight in the Morning. Dream’d that I punted to Mr. Froth.

So, the gambling sense was firmly in place by the early eighteenth century. It isn’t until the twentieth century that we see punter generalize. By 1934 it had come to mean a con man’s mark. Philip Allingham’s 1934 book Cheapjack defines punter as:

Punter: A grafter’s customer, client or victim; a “sucker.”

But it need not be that blatant. Punter could just mean the client or customer of a less-than-reputable enterprise. Xavier “Gipsy” Petulengo’s 1936 A Romany Life, about his life traveling and selling various herbal nostrums and cures:

I was heading south to Kentucky. The negro population was getting thick at each move. But they were fairly good “punters” for my pills, and somehow a negro has that instinctiveness about him that “nature's way is the right way,” and I found that the negroes were in many ways superior to white folk. They usually listened to an explanation without sarcasm and heckling, as is usual with a white crowd. We generally know these hecklers. They are mostly people who are in a business to which naturally the herbalist is a gentle rival, but we generally get the best of an argument by saying that the ancients of the Biblical days took herbs as medicine many years before the multiple drug store opened up a branch in their High Street.

No, punter did not make its way into American slang; it remains distinctly British. While the people Petulengo was describing are American, he himself is English and uses British terms, as you can also see in his use of High Street.

And punter would come to mean a prostitute’s client. From Stanley Jackson’s 1946 Indiscreet Guide to Soho:

The professional tarts [...] rarely pay for a drink and some club proprietors encourage them to bring in their “punters” or clients.

And on 15 March 1970 the London Sunday Times published an interview with a young prostitute that used the term several times:

Sally is only eighteen but she’s been a prostitute three years. She has a bank account at Lloyds and is making up to £30 a night. She has a pixie face, short black hair and big dark eyes. Her face is very white, partly because it rarely sees the sun, partly from too much make-up. Sally is still young, pert and pretty. But if the price is right, she’ll do “anything a punter wants.”

[...]

Why do I do it?—Money, that’s all. A punter to me isn’t a man. He’s just a bloke with some money and I’m trying to get it off ’im. Next day I wouldn’t recognise ’im in the street. I never get any sexual pleasure from it. It’s just a day’s work. Besides, most of the blokes are so old and ugly.

[...]

I spend my money like water, mostly on clothes. Then there’s the cost of the hotel room. I pay two quid a night for that. And there’s jewellery and make-up, and food. And rubbers, too. I always make the punter wear a rubber, even though I can’t have children myself the doctor says. I’ve never had a disease. I go for a check-up at least once a month.

The origin of punter may be somewhat mysterious, but its semantic development is clear, from gambler to someone who engages in a variety of other scams or vices.

Sources:

Addison, Joseph. The Spectator, no. 323, 11 March 1712, 8. Eighteenth Century Collections Online (ECCO).

Allingham, Philip. Cheapjack. New York: Frederick A. Stokes, 1934, xv. HathiTrust Digital Archive.

D’Urfey, Thomas. The Campaigners: or, the Pleasant Adventures at Brussels. London: A. Baldwin, 1698, 3.1, 24. Early English Books Online (EEBO).

———. “Hell Beyond Hell: or the Devil and Mademoiselle.” Tales Tragical and Comical. London: Bernard Lintott, 1704, 94. Eighteenth Century Collections Online (ECCO).

Green’s Dictionary of Slang, 2021, s.v. punter, n.

Leland, Timothy. “Look!” The Sunday Times (London), 15 March 1970, 60. Gale Primary Sources: Sunday Times Digital Archive.

Oxford English Dictionary, third edition, September 2007, modified March 2020, s.v. punter, n.1; modified June 2020, s.v. punt, v.1; modified December 2020, s.v. punt, n.2, punto, n.3.

Petulengro, Xavier “Gipsy.” A Romany Life. New York: E.P. Dutton, 1936. 203. HathiTrust Digital Archive.

The Royal Game of the Ombre. London: William Brook, 1660, 4. Early English Books Online (EEBO).

Sandys, Edwin. Articles to Be Enquired of in the Visitation of the Dioces of London. London: William Seres, 1571, sig. B.1.r–v. Early English Books Online (EEBO).

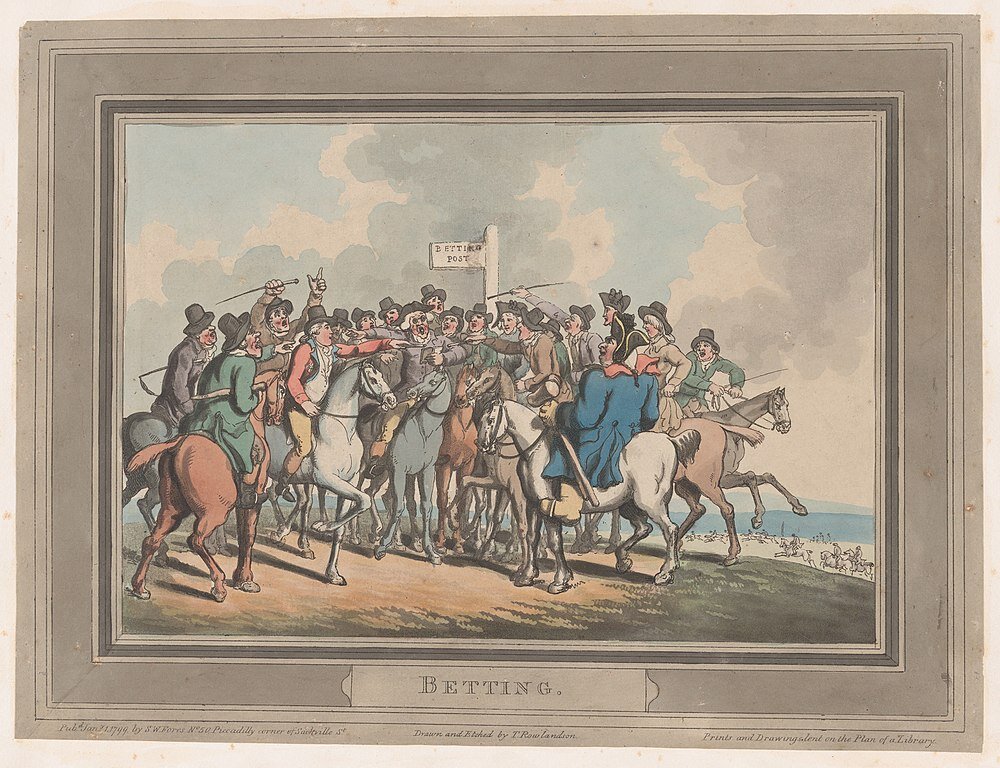

Image credit: Thomas Rowlandson, “Betting,” 1799. Elisha Whittelsey Collection, Metropolitan Museum of Art. Public domain image.