2 May 2022

Pneumatic is a seventeenth-century borrowing from the Latin pneumaticus and the Greek πνευματικός. The Latin word is originally also a borrowing from the Greek, but English takes the word from both languages directly. In ancient Greek, the word referred to the air, wind, or breathing, but in Hellenistic (e.g., New Testament) Greek it also acquired a sense of the spirit or soul. This semantic pattern is repeated in the Latin, referring to air pressure in the classical period but expanding to include the spirit in the fifteenth century.

The earliest appearance of the word in English that I have found is as an adjective describing a person, presumably someone with some sort of pulmonary affliction such as asthma. It appears in a 1612 translation of Thomas de Fougasse’s Generall Historie of the Magnificent State of Venice:

This man whosoeuer he was, dealt with one named Calergo, the Pneumaticke, and hauing set before him the entire dominion of the Island, perswaded him to kill all those, who did continue in the Venetians obedience; and for this purpose to draw great numbers of Greekes to his partie. This Calergo consented thereunto, and came first of all to Mopsilla, a pleasant countrey house, where he assailed Andrea Cornari, and slew him.

(As far as I can tell, there is no French equivalent to pneumatic in Fougasse’s original. The word is an addition in the English translation.)

But a little more than a decade later, pneumatic was being used to refer to things spiritual or related to the church. (The root of spirit relates to breath, also giving us words like aspiration and respiration.) Here is a use of pneumatic to refer to the hierarchy of the church, from another translation, this time in a 1624 rendering of George Goodwin’s Babels Balm, an anti-Catholic satire:

All things are iudg'd by the Spirituall man:

Ergo, iudge Popes, pneumaticke-Lords, none can.

(I have not been able to locate the original Latin text to see if the word appears there.)

And by 1654 pneumatic was being used to refer to the physical mechanics of air. From Walter Charleton’s Physiologia Epicuro-Gassendo-Charltoniana:

The Reasons of Rarity and Density thus evidently Commonstrated, the pleasantness of Contemplation would invite us to advance to the examination of the several Proportions of Gravity and Levity among Bodies, respective to their particular Differences in Density and Rarity; the several ways of Rarifying and Condensing Aer and Water; and the means of attaining the certain weights of each, in the several rates, or degrees of their Rarifaction and Condensation; according to the evidence of Aerostatick and Hydrostatick Experiments: but in regard these things are not directly pertinent to our present scope and institution, and that Galilaeus and Mersennus have enriched the World with excellent Disquisitions upon each of those sublime Theorems; we conceive ourselves more excusable for the Omission, than we should have been for the Consideration of them, in this place. However, we ask leave to make a short Excursion upon that PROBLEM, of so great importance to those, who exercise their Ingenuity in either Hydraulick, or Pneumatick Mechanicks.

In the opening years of the twentieth century, however, pneumatic acquired a new sense in American slang; it began to be used to refer to large-breasted women. The slang term was probably inspired by the pneumatic tires that were starting to appear on bicycles and automobiles. This sense appears in a 1905 O. Henry short story, The Girl and the Graft, in a passage about the utility of women in a confidence game:

“Ladies?” said Pogue, with western chivalry. “Well, not to any great extent. They don’t amount to much in special lines of graft, because they’re all so busy in general lines. What? Why, they have to. Who’s got the money in the world? The men. Did you ever know a man to give a woman a dollar without any consideration? A man will shell out his dust to another man free and easy and gratis. But if he drops a penny in one of the machines run by the Madam Eve’s Daughters’ Amalgamated Association and the pineapple chewing gum don’t fall out when he pulls the lever you can hear him kick to the superintendent four blocks away. Man is the hardest proposition a woman has to go up against. He’s a low-grade one, and she has to work overtime to make him pay. Two times out of five she’s salted. She can’t put in crushers and costly machinery. He’d notice ’em and be onto the game. They have to pan out what they get, and it hurts their tender hands. Some of ’em are natural sluice troughs and can carry out $1,000 to the ton. The dry-eyed ones have to depend on signed letters, false hair, sympathy, the kangaroo walk, cowhide whips, ability to cook, sentimental juries, conversational powers, silk underskirts, ancestry, rouge, anonymous letters, violet sachet powders, witnesses, revolvers, pneumatic forms, carbolic acid, moonlight, cold cream and the evening newspapers.”

And it appears in a T.S. Eliot poem, Whispers of Immortality, from 1919:

Grishkin is nice; her Russian eye

Is underlined for emphasis;

Uncorseted, her friendly bust

Gives promise of pneumatic bliss.

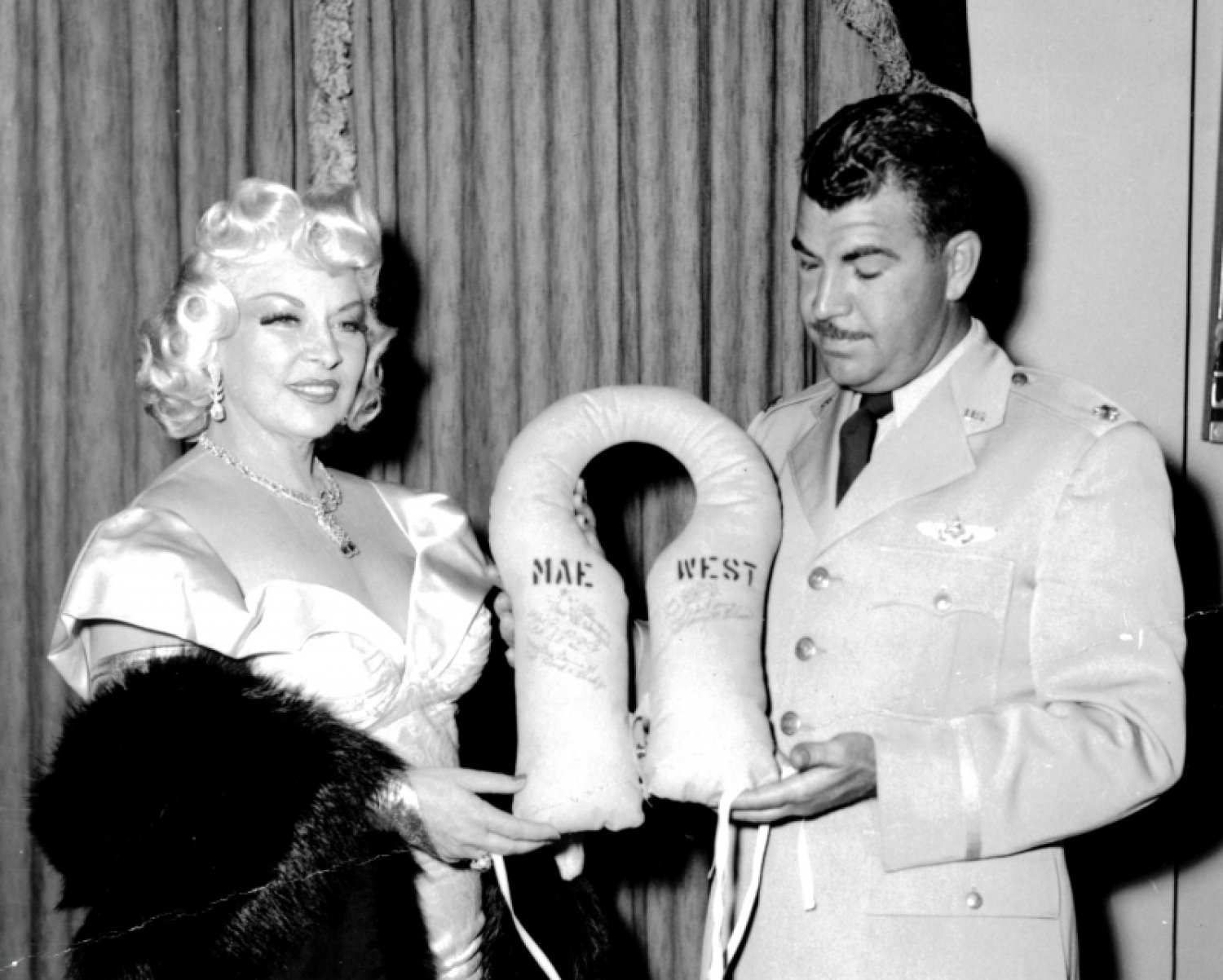

The idea here, of course, is that breasts are inflated. The same metaphor appears in the World War II slang term Mae West, referring to an inflatable life vest worn by airmen. The was well known for her busty figure, and Mae West appears in print early on in the war. It probably is older in spoken use by fliers, though. From the magazine The Listener of 11 January 1940 in an article about Royal Navy pilots:

Full flying kit consists of a combination suit like the skin of a teddy bear. On top of that goes a windproof combination suit with a high collar lined with fleece. Then comes a life-saving waistcoat. This can be inflated in a few moments by the wearer, and for some obscure reason is known technically as a “Mae West.”

These slang uses of pneumatic and Mae West were figurative. It would be a few decades before silicone implants made artificial “inflation” of breasts a reality.

Sources:

Charleton, Walter. Physiologia Epicuro-Gassendo-Charltoniana, or, a Fabrick of Science Natural. London: Thomas Newcomb for Thomas Heath, 1654, 256–57. Early English Books Online (EEBO).

Dictionary of Medieval Latin from British Sources. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2013, s.v. pneumaticus, adj. Brepolis: Database of Latin Dictionaries.

Eliot, T.S. “Whispers of Immortality.” Ara Vus Prec. London: Ovid Press, 1919, 21. HathiTrust Digital Archive.

Fougasse, Thomas de. The Generall Historie of the Magnificent State of Venice. Translated by W. Shute. London: G. Eld and W. Stansby, 1612, 217. Early English Books Online (EEBO).

———. Histoire Generale de Venise. Paris: Abel l’Angelier, 1608. Google Books.

Goodwin, George. Babels Balm: or the Honey-Combe of Romes Religion. Translated by John Vicars. London: George Purslowe for Nathaniel Brown, 1624, 32. Early English Books Online (EEBO).

Henry, O. (pseud. William Sydney Porter). “The Girl and the Graft.” The Pittsburgh Gazette (Pennsylvania), 28 May 1905, Sect. 3, page 2. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

Lewis, Charlton T. and Charles Short. A Latin Dictionary. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1879, s.v. pneumaticus, adj. Brepolis: Database of Latin Dictionaries.

“The Navy that Flies.” The Listener, 11 January 1940, 56. Gale Primary Sources: Listener Historical Archive, 1929–1991.

Oxford English Dictionary, third edition, September 2006, s.v. pneumatic, adj. and n.; March 2000, s.v. Mae West, n.

Image credit: Unknown photographer, 1954. Fair use of a presumably copyrighted image to illustrate the topic under discussion.