6 February 2023

Is Pluto a planet? The debate over that question has been ongoing since 2006, when the International Astronomical Union (IAU) demoted Pluto in its nomenclature scheme, leaving the solar system with only eight IAU-recognized planets. The IAU’s decision was both scientifically and linguistically suspect, as can be seen from an examination of the history of the word planet and the process by which lexicographers come up with definitions—after all, if you want to create a definition of a term, you should go to the professionals.

Our word planet ultimately comes from the Greek πλάνης (planēs), stem πλάνητ- (planēt-), meaning wanderer, a reference to the motion of the those celestial objects relative to the stars. The word came into English via the Anglo-Norman planete (attested in that language from c.1185) and the Latin planeta. While the etymology of the word has never been in doubt, exactly what objects qualify as planets has continually changed over the centuries.

The Latin planeta was known in pre-Conquest England, although it was not fully incorporated into Old English. Ælfric, in his De temporibus anni (Regarding the Seasons of the Year), a text on astronomy written in 992, records:

Seo sunne, & se mona, & æfensteorra, & dægsteorra, & oðre ðry steorran ne sind na fæste on ðam firmamentum, ac habbað heora agenne gang on sundron. Þa seofon sind gehatene Septem planete.

(The sun, the moon, the evening star, the morning star, and three other stars are not fixed in the firmament, but have their own path apart. The seven are called Septem planete.)

The phrase septem planete, here, has Latin inflections, while the rest of the words are English. And note Ælfric and his contemporaries considered the sun and moon to be two of the seven planets; the others being the five planets visible to the naked eye from the Earth’s surface: Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn. The Earth was not considered to be a planet, even though early medieval astronomers knew it to be a sphere, a fact that Ælfric acknowledges elsewhere in the work.

Byrhtferth’s Enchiridion (Handbook), another pre-Conquest book on astronomy, written c. 1011, contains the following:

Þa steorran þe man hæt planete on Lyden and on Grecisc apo tes planes (hoc est ab errore) oðre hwile hig beoð on eastende þære heofone swa sunne byð dæghwamlice.

(The stars which people called planete in Latin and in Greek apo tes planes (that is, from wandering) are sometimes at the eastern end of the heaven, as the sun is very day.)

It isn’t until the Middle English period that planet starts appearing in English works as a naturalized word. The South English Legendary, a collection of saint’s lives written c.1300 records the word:

Eiȝte firmamenz þare beoth: swuche ase we i-seoth,

þe Ovemeste is þe riȝtte heouene: in ȝwan þe steorrene beoth—

for godes riche is þare a-boue: þat last with-outen ende;

þare-be-neoþe beoth seoue fermamenz: þat euerech of heom, i-wis,

One steorre hath with-oute mo: þat planete i-cleoped is.

Ichulle nemmen heore seoue names: and formest bi-guynne hext:

Saturnus is al a-boue: and Iupiter sethþe next,

þanne Mars bi-neoþen him: and sethþe þe sonne is,

Venus sethþe, þe clere steorre: Mercurius þanne i-wis,

þat wel selden is of us i-seiȝe: þe Mone is next þe grounde.(There are eight firmaments, such as we see. The highest is the genuine heaven, in which are the stars—for God’s kingdom is above that, which lasts without end. Beneath that are seven firmaments, each one being home, in fact, to just one star, which is called a planet. I will list their seven names, beginning with the highest. Saturn is above all, and Jupiter follows next. Then Mars is beneath him, and then follows the sun. Venus, the bright star, follows, then, in fact, Mercury, which is very seldom visible to us. The moon is next to the ground.)

This definition held until the Copernican revolution. The heliocentric solar system promulgated by Copernicus and Galileo necessitated a redefinition of planet. The sun and moon were excluded from the list, and Earth was added. In a 1640 book, John Wilkins, who would go on to become the Bishop of Chester and one of founders of the Royal Society, outlined this new astronomical system (and hypothesized life on the moon and other planets):

I have now cited such Authors both ancient and moderne, who have directly maintained the same opinion. I told you likewise in the Proposition that it might probably be deduced from the tenents of others: such were Aristarchus, Philolaeus, and Copernicus, with many other later Writers who assented to their hypothesis; so Ioach. Rhelicus, David Origanus Lansbergius, Guil. Gilbert, and (if I may beleeve Campanella) Innumeri alij Angli & Galli, Very many others, both English and French, all who affirmed our Earth to be one of the Planets, and the Sunne to be the Center of all, about which the heavenly bodies did move. And how horrid soever this may seeme at the first, yet is it likely enough to be true, nor is there any maxime or observation in Opticks (saith Pena) that can disprove it.

Now if our earth were one of the Planets (as it is according to them) then why may not another of the Planets be an earth?

The fifth edition of that work, published in 1684, would add as a subtitle, “A Discourse Concerning a New Planet, Tending to Prove, That ’tis Probable Our Earth Is One of the Planets.”

Over the succeeding centuries the list of planets expanded and contracted. Uranus and Neptune were added upon their discovery. Ceres was originally considered to be a planet, before being demoted to mere asteroid. The planet Vulcan (not the one from Star Trek), believed to orbit the sun closer than Mercury, was considered to be a planet for a while, until it was shown to not exist. Pluto, the first of the Kuiper Belt objects to be discovered, was added to the list upon its discovery in 1930, and for the rest of the twentieth century the list consisted of nine planets: Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, Neptune, and Pluto.

All the while, astronomers got along just fine without formulating a definition of exactly what constituted a planet. The definition, like all the definitions found in general dictionaries, was determined by common usage.

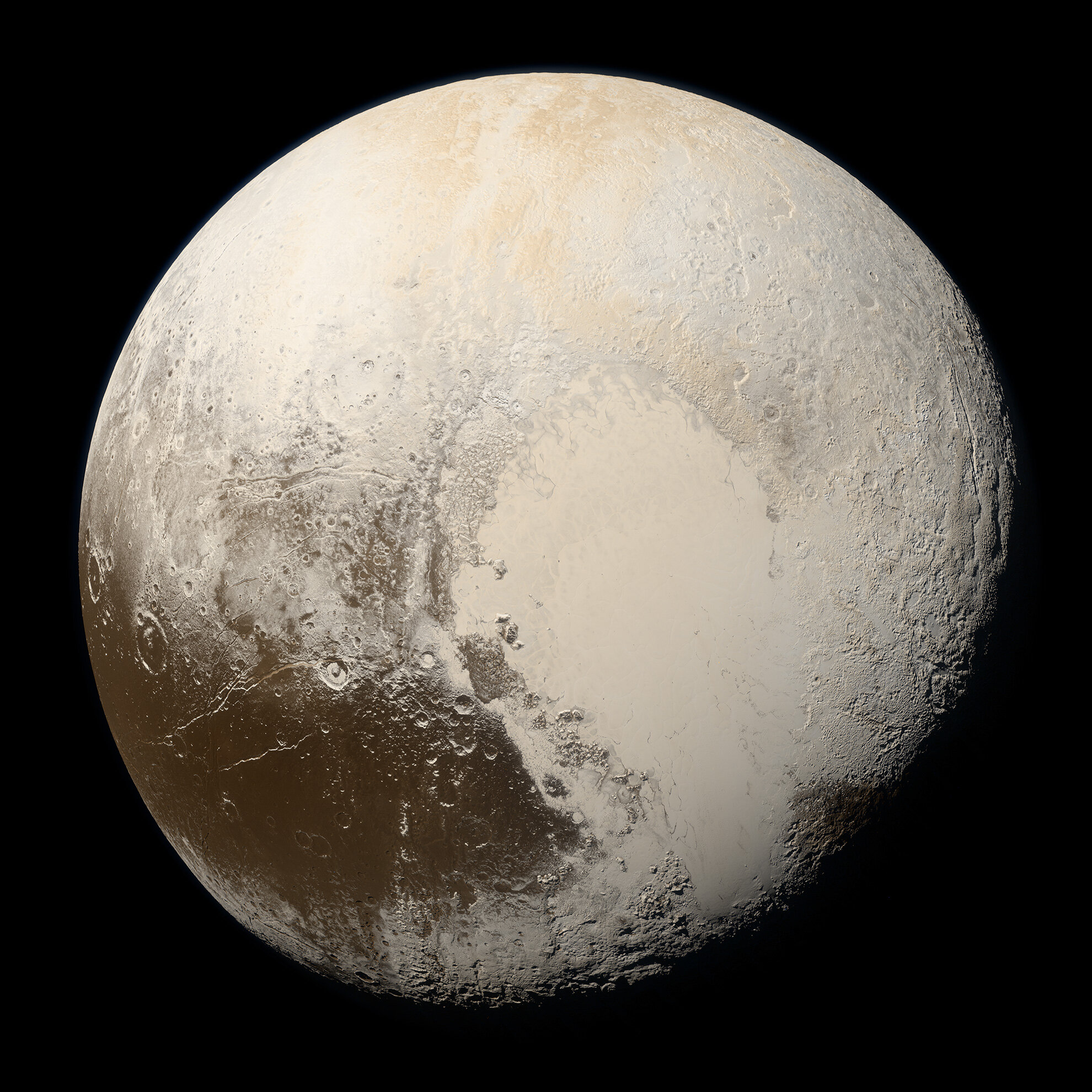

But by 2005, the discovery of additional Kuiper Belt objects, Eris, Makemake, and Haumea, prompted a problem. Were these to be considered planets too? Eris is roughly the same size as Pluto, and therefore should be considered in the same class. (The New Horizons probe has given us a good measurement of Pluto’s size, but that of Eris is continually being revised up and down as new observations come in. Some days it’s bigger than Pluto; on others it’s smaller.) And there will likely be hundreds of Kuiper Belt objects discovered in coming years, with quite a few being the same size as Pluto and Eris. The list of planets could grow to be unmanageable.

In 2006 the International Astronomical Union (IAU) promulgated a new definition. To be considered a planet an object had to:

orbit the sun

achieve hydrostatic equilibrium (i.e., have a round shape)

have cleared its neighborhood of other objects.

Pluto and Eris failed this last criterion. The list of planets was officially capped at eight.

The definition succeeded in keeping the list manageable. And if the definition had been restricted to the province of what kind of names to assign to planets, that would be fine. Arbitrary naming conventions are the norm—for instance, the moons of Uranus, but not of other planets, are named for characters from Shakespeare. But the definition was not just used for naming; it was applied as a general classification. And as such, the definition is both scientifically useless and linguistically suspect.

First, by saying planets must orbit the “sun,” it arbitrarily limits the planets to our own solar system. According to the definition, there are no other planets in the universe—the IAU dubs planets outside the solar system as exoplanets, a term that dates to 1992. But one of the fundamental tenets of science is that the same rules operate throughout the universe. It makes no scientific sense to have different terms for the same class of object depending on where they exist. Second, hydrostatic equilibrium depends on both mass and composition, so a more massive rocky object might fail the criterion, while a smaller gaseous body might meet it. And whether an object can “clear its neighborhood” depends not only on size, but also on distance from the sun. Mercury, Venus, Earth, and Mars would not have sufficient mass to clear their neighborhood if they orbited in the Kuiper Belt. And planets can shift their orbits over their lifespans, so it is possible for an object to be a planet in one epoch and not one in another. Ganymede, the largest moon of Jupiter and of the solar system, has far more in common with rocky Mercury than it does with the gas giant Jupiter, yet, according to the IAU definition, Mercury and Jupiter are in the same category and Ganymede is not.

Those solar objects that fail to make the planetary cut have been dubbed dwarf planets. Currently there are about a dozen objects that meet the official criteria for this category, including Pluto, Eris, and the asteroid Ceres. But dwarf planet, like its larger cousin, is not a new term and what constitutes a member of the category has also shifted over the years. Dwarf planet was first used in 1839 in reference to the asteroids in an early science-fiction book, A Fantastical Excursion into the Planets:

But know I am utterly unable to tell on which of the four so wondrous—and yet so neatly divided parcels, I had just alighted, as my spark merely noticed that our landing had been on the territory of one of the dwarf planets, which our astronomers had given in lease to four antiquated divinities, namely to Vesta, Juno, Ceres and Pallas.

Over the years various objects have been considered dwarf planets, including Earth, Venus, and Mars. Which makes sense when you compare them to a behemoth like Jupiter.

And linguistically, both exoplanets and dwarf planets are planets; the exo- and dwarf being mere modifiers. Moreover, usage, even that by professional astronomers, does not adhere to the IAU’s definition. Astronomers routinely use planet, with no modifiers, to refer to exoplanets. For example, there is this from the Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific published in January 2020:

α Centauri A is the closest solar-type star to the Sun and offers an excellent opportunity to detect the thermal emission of a mature planet heated by its host star.

The IAU definition dominates the discussion currently, but it will assuredly be edged aside eventually because it makes no sense, either scientifically or lexicographically. Planets have always been those things that people call planets, and the list of planets has expanded and contracted with the fashion of the age. The logic is circular, but that’s how language works. If the IAU definition created a consistent and scientifically useful classification, then it would be a good technical definition. But it does not.

Perhaps the best method to determine whether or not a celestial object should be dubbed a planet is the Star Trek method—if it would look like a planet if seen from the viewscreen of an orbiting starship Enterprise, then it is a planet.

Sources:

Ælfric, De temporibus anni. Heinrich Henel, ed. Early English Text Society, O.S. 213. London: Oxford UP, 1942.

Anglo-Norman Dictionary, 2017, s.v. planete, n.

Beichman, Charles, et al. “Searching for Planets Orbiting α Cen A with the James Webb Space Telescope.” Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific, January 2020, 1. JSTOR.

Byrhtferth, Enchiridion. Peter S. Baker and Michael Lapidge, eds. Early English Text Society S.S. 15. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1995.

A Fantastical Excursion into the Planets. London: Saunders and Otley, 1839, 98. Archive.org.

Horstmann, Carl, ed. “Of the Eight Firmaments and the Seven Planets.” The Early South-English Legendary. Early English Text Society, O.S. 87. London: N. Trübner, 1887, 312–13, lines 413–23. HathiTrust Digital Archive. Oxford, Bodleian MS Laud 108.

Middle English Dictionary, University of Michigan, 2019, s. v. planet(e (n.(1))

Merriam-Webster.com, s.v. exoplanet.

Oxford English Dictionary, third edition, June 2006, s.v. planet, n.; June 2009, s.v. dwarf planet, n.; September 2017, s.v. exoplanet, n.

Wilkins, John. A Discourse Concerning a New World & Another Planet in 2 Books, third impression. London: John Norton for John Maynard, 1640, 90–91. Early English Books Online (EEBO).

Zimmer, Ben. “New Planetary Definition a ‘Linguistic Catastrophe’!” Language Log (blog), 25 August 2006.

Image credit: NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Southwest Research Institute/Alex Parker, 2015. Public domain image.