22 March 2021

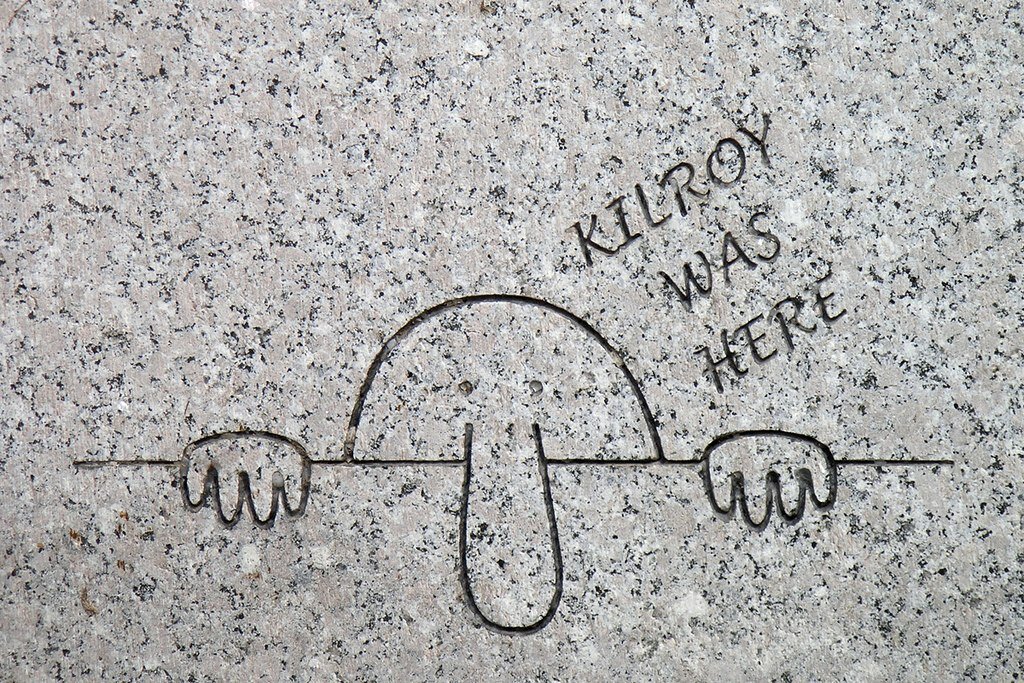

In the 1940s, Kilroy was here was a phrase scrawled on walls, vehicles, and other pieces of equipment around the world, from French villages to Pacific atolls, wherever American service men and women were stationed during World War II. Kilroy was something of a Scarlet Pimpernel, appearing everywhere and nowhere at the same time. At some point, perhaps after the war, Kilroy started appearing alongside the drawing of his British counterpart Mr. Chad.

The first citation of Kilroy was here in the Oxford English Dictionary is from the Saturday Evening Post of 20 October 1945. While it is not the first appearance of the phrase in print, it does give an excellent description of the ubiquity of the graffito:

When an Army Air Forces lieutenant entered the bedroom of a furnished house in Long Beach, California, which the Army’s 6th Ferrying Group had rented for him, he saw a baby’s crib. On the crib hung a hand-lettered sign which asserted: KILROY SLEPT HERE. “Well,” said the lieutenant softly, “I’ll be damned.”

With this comment about the Army Air Forces’ celebrated man of mystery, the flier was repeating himself. He had made a similar comment after landing in Accra, Africa, after hopping the Atlantic from Natal, and again at Karachi, India, and still again when he arrived in China on his first flight over the Hump from the Mohanbari airfield in Assam.

In those faraway places messages from Kilroy had greeted him, not on a baby’s crib but from the walls of rooms and the doors of hangars and from all manner of other strange places wehre a communication could be written or hung. In Australia, New Guinea, the Philippines, on islands all over the Pacific, he had read the record of the man who had been everywhere and, apparently, invariably had been there first. Wherever he was, Kilroy had been there and left his mark behind: KILROY WAS HERE, or KILROY PASSED THROUGH, or YOU’RE IN THE FOOTSTEPS OF KILROY.

In his diary entry for 5 September 1945, Major Ben Kaplan, one of the first Americans to arrive in Japan after the surrender, has this account of how fast the graffito appeared in that country and of the various places he had seen it during his wartime service:

A sign on one of the hangars: “Kilroy was Here.” This was the first I’ve seen in Japan, but Kilroy is a mythical character one is likely to meet anywhere in the world. Don’t know who “invented” the gag, but one sees the signs, or scrawlings everywhere. Sometimes it’s “Kilroy Slept Here,” or variations thereof; “Kilroy’s Island—Discovered by Kilroy”; “Kilroy Doesn't Live Here Anymore.” In Bengazi [sic] once I saw a sign which read: “Kilroy’s Home Town.” There was an oversized “Kilroy Kurrency” note under a glass desktop at Hickam Field, Hawaii, when we passed through there.

The phrase probably originated c. 1943 by some anonymous serviceman, but the earliest use in print that I’m aware of is from the air base newspaper Sheppard Field Texacts on 21 April 1945:

Who is Kilroy? What a one man campaign! He seems destined to go down in history along with Foo and Novschmozkapop as a family by word.

Roger Angell, who later became famous as an essayist, baseball writer, and fiction editor for the New Yorker, wrote the following on 26 June 1945 in Brief, a publication of the U.S. Army Air Forces, Pacific Ocean Areas:

Who is Kilroy?

Kilroy is the guy who just stepped out of the orderly room as you came in. Kilroy was in the latrine, but he left before you got there. He was in your messhall, but didn’t like the food and left before you showed up. He’s the tail gunner that doesn’t answer when you call him on the intercom; he’s the character that bought the last lighter at the PX, just before you went over to buy one.

This wacky routine is the latest AAF gag, that is spreading fast from the States. Every bulletin board, officer’s club and latrine in the States has a notice up about Kilroy—the imaginary character that no one ever catches up to. Planes have been named for him, but nobody has ever seen him. Notices on bulletin boards which say to turn in laundry at 0700 also announce that Kilroy turned his in at 0645.

Kilroy, as far as we can find out, never got to the ETO. The farthest east he ever got was Jamaica. But he is on his way here from home, along with all the new pilots that are heading Pacific-ward. His latest non-appearance occurred somewhere between California and Oahu. A B-29 crew, flying out, got into a radio conversation with a ship. The radioman, just as he was about to sign off, asked the the sailor if he had seen anything of Kilroy. “Yeah,” said the sailor. “We passed a sign in the water a few miles back. It said ‘Kilroy ditched here.’”

Kilroy will be here any day, but you won’t be seeing him.

Angell was mistaken about Kilroy not making it to Europe, and there is this early use in the Seattle Times of 29 July 1945 that shows that Kilroy was not limited to the air force:

The most notorious character at Fort Lawton these days is a soldier—(or something)—named Kilroy—who isn’t there.

The one-time existence of Kilroy, who has been described as everything from an infantry private, first-class, to a white rat, is resumed from numberless chalked signs, scattered about the fort, which read:

“Kilroy slept here.”

“Kilroy drove this truck.”

“Kilroy got clipped here.” At the barber shop) [sic]

“Kilroy got the needle here.” (At the medical processing center.)

Kilroy is an uncommon—but far from unknown—surname in North America, but who the Kilroy was, if he even was a real person, is unknown. There are multiple claims as to the original Kilroy, but none can be verified. For instance, there is this 24 November 1945 story in the San Francisco Chronicle that credits an Army Airman Francis J. Kilroy with being the original:

HERE IS KILROY: Thanks to Navy Lieutenant John M. Lamb of Berkeley, Newsman Bill Walsh, one or two anonymous contributors and some one who calls himself “Pipefitter Pete,” we’re able to identify the young man who inspired, on a global scale, the appearance of all the signs reading, “Kilroy was here.” We understand he’s been identified before, but for those who, like us, came in late, here is the word on Kilroy.

In the first place, he is AAF Sergeant Francis J. Kilroy Jr., of 967 Broadway, Everett, Mass. In 1943, at the Boca Raton Army Air Field in Florida, he struck up a friendship with Sergeant James Maloney of Philadelphia. One day, Kilroy became a flu victim and was hospitalized. When he learned how soon his friend would be out of the hospital, Maloney returned to his barracks and for no good reason scrawled on the bulletin board: “Kilroy will be here next week.” A month later, Maloney and Kilroy were transferred to different fields, but the Kilroy signs appealed to Maloney, and he kept on scrawling them when he thought of it and on anything that happened to be handy. They caught on, and soon every one was doing it in various parts of the world and various theaters of war. The contagion seems to be very similar to that which followed the American Legion convention of several years ago, which had every one exclaiming, “Where’s Elmer?” for months afterward.

Anyway, to wind up the part about Kilroy, the sergeant spent 10 months in Italy with a bomb group and received a distinguished unit citation and five battle stars. As of a few weeks ago, he was awaiting discharge at Davis-Monthan field, near Tucson, and may by now be back in civilian clothes.

And a little over a year later, the New York Times of 24 December 1946 credits a shipyard inspector named James J. Kilroy with being the original:

In brief, Mr. [James J.] Kilroy’s claim is based on the following:

During the war he was employed at the Bethlehem Steel Company’s Quincy shipyard, inspecting tanks, double bottoms and other parts of warships under construction. To satisfy superiors that he was performing his duties, Mr. Kilroy scribbled in yellow crayon “Kilroy was here” on inspected work. Soon the phrase began to appear in various unrelated places, and Mr. Kilroy believes the 14,000 shipyard workers who entered the armed services were responsible for its subsequent world-wide use.

It’s possible that both are the progenitors of Kilroy was here, or perhaps neither and that it was someone else who inspired all that graffiti.

As mentioned above, the simple drawing of a man peering over a wall has been associated with Kilroy, but the drawing was originally of his British counterpart, Mr. Chad, or simply Chad. The British Mr. Chad was typically accompanied with the interrogative phrase What! No ____? or Wot! No ____? with the blank being filled by whatever happened to be in short supply that week. The origin of the name Mr. Chad is just as mysterious as Kilroy, but we can pinpoint the origin of the drawing.

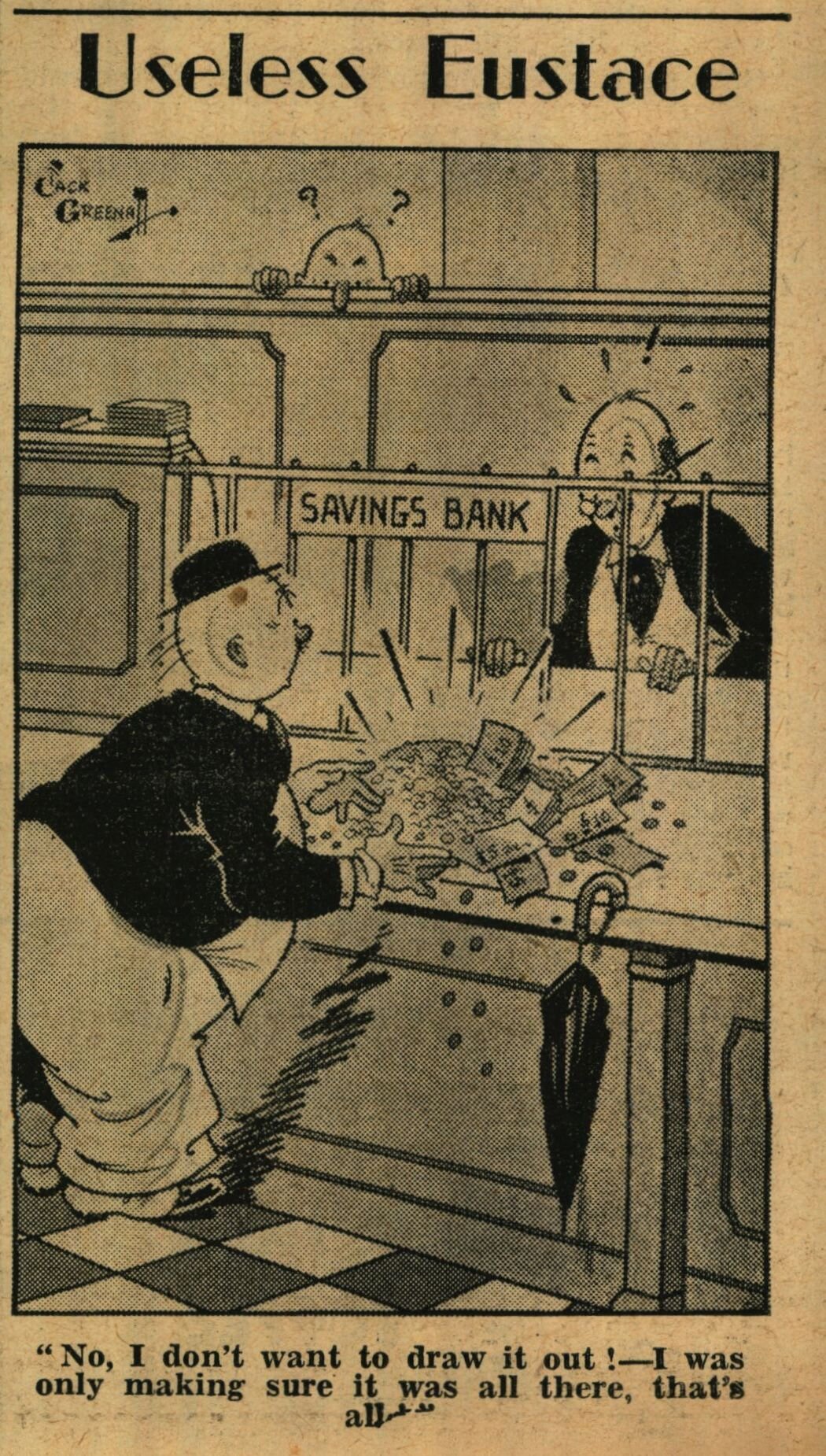

The drawing was created by British cartoonist and erstwhile drawing instructor Jack Greenall in the mid 1920s, early in his career when he was employed at a technical drawing school, as an exercise for his students in drawing simple forms. The figure first saw print when Greenall included the image in a Useless Eustace cartoon published in London’s Daily Mirror on 11 December 1937. The oft-included caption of “Wot! No ____?” would be added later, as commentary on wartime shortages.

Like Kilroy, the name Mr. Chad would not be documented in print until the very end of the war, but there is an intriguing London Times crossword clue for 14 July 1941. The clue reads, “The weight of Mr. Chad,” and the answer was drachm, an anagram for Mr. Chad. This crossword clue is probably just coincidence, but we cannot rule out that Mr. Chad was in oral circulation at this early date and inspired the clue.

The first unambiguous use of the name in print is in the Gloucestershire Echo of 6 September 1945:

A local member of the Association of Army Radio Mechanics, a newly-formed ex-Servicemen’s Association, Cfn. W. Cole, of 11, White Hart-street, Cheltenham, tells us that the president is the mysterious “Mr. Chad,” well known to all Army and ex-Army radio mechanics.

The first recorded appearance of Mr. Chad was when he was with the No. 2 Radio Mechanics School when this was located at Oakley Farm, Cheltenham.

The “first recorded appearance” mentioned in the article is unknown and may simply refer to someone’s recollection of having seen it at the school. But the explanation of the origin being at the radio mechanics school is probably incorrect, although one cannot completely discount the idea that Greenall’s drawing exercise from the 1920s continued to be used by other technical drafting instructors. The idea that the image stems from the Greek letter omega, the symbol for electrical resistance, or from a drawing of a simple electrical circuit would seem to be after-the-fact groping for an explanation.

Another early appearance is in The Daily Mirror of 10 September 1945:

Who is Mr. Chad? You probably don’t know, just as you didn’t know what a Gremlin was when you first heard the name. But for several years now Mr. Chad’s portrait has been appearing regularly on the walls—inside and outside—of Service huts and vehicles.

In the end, we’ll probably never know who the original Kilroy was or the name of the Tommy who first scrawled “Wot! No?” under a drawing of a man peering over a wall. In a way, it’s more appropriate that Kilroy and Mr. Chad remain mysterious. He is every soldier, sailor, and airman who served.

Sources:

Angell, Roger. “File 13.” Brief, 26 June 1945, 18. Google Books.

Associated Press. “Transit Association Ships a Street Car to Shelter Family of ‘Kilroy Was Here.’” New York Times, 24 December 1946, 18. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

French, William F. “Who is Kilroy?” Saturday Evening Post, 20 October 1945, 6. EBSCOhost Academic Search Ultimate.

Green’s Dictionary of Slang, 2021. s.v. chad n.

“How Mr. Chad was born.” Daily Mirror (London), 10 September 1945, 7. Gale Primary Sources: Mirror Historical Archive.

Kaplan, Ben Z. “Tojo Doesn’t Live Here Any More.” Free World, 10.6, December 1945, 36. HathiTrust Digital Archive.

Mahaffay, Robert. “Kilroy ‘Gets Around’ at Fort Lawton.” The Seattle Times, 29 July 1945, 14. Newsbank: America’s Historical Newspapers.

“Mr. Chad is 20 Years Old.” Daily Mirror (London), 30 January 1946, 1. Gale Primary Sources.

O’Brien, Robert. “San Francisco.” San Francisco Chronicle, 24 November 1945, 9. Newsbank: America’s Historical Newspapers.

Oxford English Dictionary, second edition, 1989, Kilroy, n.

Shapiro, Fred. “More Precise Information on Antedating of ‘Kilroy.’” ADS-L, 1 April 2016.

“Squadron T.” Sheppard Field Texacts (Texas), 21 April 1945, 9. NewspaperArchive.com.

“Times Crossword Puzzle No. 3,552.” The Times (London), 14 July 1941, 6. Gale Primary Sources: Times Digital Archive.

“To-Day’s Gossip.” Gloucestershire Echo, 6 September 1945, 3. Gale Primary Sources: British Library Newspapers.

Image credits: WWII Memorial engraving: Luis Rubio, 2006, licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license; Jack Greenall, “Useless Eustace, Daily Mirror, 11 December 1937, 8. Gale Primary Sources: Mirror Historical Archive. Fair use of a copyrighted image to illustrate a point under discussion.