3 March 2021

Jerk has many meanings, but most stem from an echoic verb meaning to make a sharp movement. From there, it would generalize into any sharp movement, especially a pull or tug. To pull a beverage from a tap would give rise to the soda jerk, and tugging on a man’s penis would spawn jerk-off, which would be clipped and bowdlerized to refer to a contemptible person.

The verb to jerk makes its appearance in the early fifteenth century. It starts out as shoemaking jargon meaning to stitch tightly, undoubtedly from sharp tugging on the threads. It appears in an agreed list of prices promulgated by the cordwainer’s guild in York, England, c. 1430. The entry is Latin, except for the word yerked or jerked:

Item, pro sutura xij parium sotularum yerkyd ad manum, iiij d.

(Item, for stitching 12 pairs of shoes, jerked by hand, 4 d.)

From the sixteenth into the eighteenth century when the sense became obsolete, to jerk could mean to strike, especially with a rod or whip. From a 1550 religious tract, A Spyrytuall and Moost Precyouse Pearle:

Fyrst he teacheth vs hys wyll thorowe the preachynge of hys word, and gyuyth vs warnyng. Now, if so be, that we wyll not folow hym, than he beateth and gierketh vs a lytle wyth a rodde, as some tyme wyth pouerty, some tyme wyth sycknes and dyseasys or with other afflyccyons, whych shoulde be namyd & estemyd as nothyng els, but chylderns roddys or the wandys of correccyon.

(First he teaches us his will through the preaching of his word and gives us warning. Now, if it happens that we will not follow him, then he beats and jerks us a little with a rod, sometimes with poverty, sometimes with sickness and diseases or with other afflictions, which should be named and esteemed as nothing else but children’s rods or the wands of correction.)

The sense of any tug or sharp movement, not just one at the shoemaker’s last, was in place by the late sixteenth century. From a 1582 translation of Robert Parsons’s An Epistle of the Persecution of Catholickes in Englande:

Yet forsoothe he geueth vs fayre woords, & will nedes beare vs on hand that he will support vs with his faithfull assista[n]ce. And thereupo[n] he steppeth furth, and vp he Ierketh his hands, & white of his eyes to heaue[n] ward, (as his maner is) and (full deuoutlye lyke a good man) he there vndertaketh the defense of the cause: but of what cause I pray yow? forsoothe euen of that same cause, which before (like an apostata) he had betrayed and forsaken, and made his bragge thereof when he had so done.

(Yet truly he gives us fair words, and will, if necessary, profess to us that he will support us with his faithful assistance. And thereupon he steps forth, and he jerks his hands upward, & the white of his eyes heavenward (as is his manner), and (very devoutly like a good man) he there undertakes the defense of the cause: but of what cause, I pray you? Truly, even of that same cause, which before (like an apostate) he had betrayed and forsaken, and boasted thereof when he had done so.)

To jerk-off, meaning to masturbate, especially by a man, is in place by the mid nineteenth century, the added off referring to completion of the act by ejaculation. It’s recorded in an 1865 book titled Love Feast by a writer with the nom de plume of Philocomus (literally “love of merry-making”):

I'll jerk off, thinking of thee.

The adjective jerk-off, referring to something that is contemptible, was in place by the 1930s, but is likely older—slang senses can rarely be dated exactly, as they are in oral use for some time before seeing print, especially overtly sexual ones, which editors and publishers tend to censor. It appears in a 1 March 1937 letter by humorist and screenwriter S. J. Perelman:

We stayed in town most of the summer after I saw you, working away on that jerk-off musical and hating it more and more; finally finished it and sawed ourselves off around the first week last August.

Jerk, meaning a contemptible person, is recorded a few years earlier than the contemptible sense of jerk-off, but it is likely a clipping of the latter. In this case the epithet jerk appears in Henry Roth’s 1934 novel Call it Sleep:

Jerk I shidda said. Cha!

And it’s recorded in Albin Pollock’s 1935 dictionary of criminal slang:

Jerk, a boob; chump; a sucker.

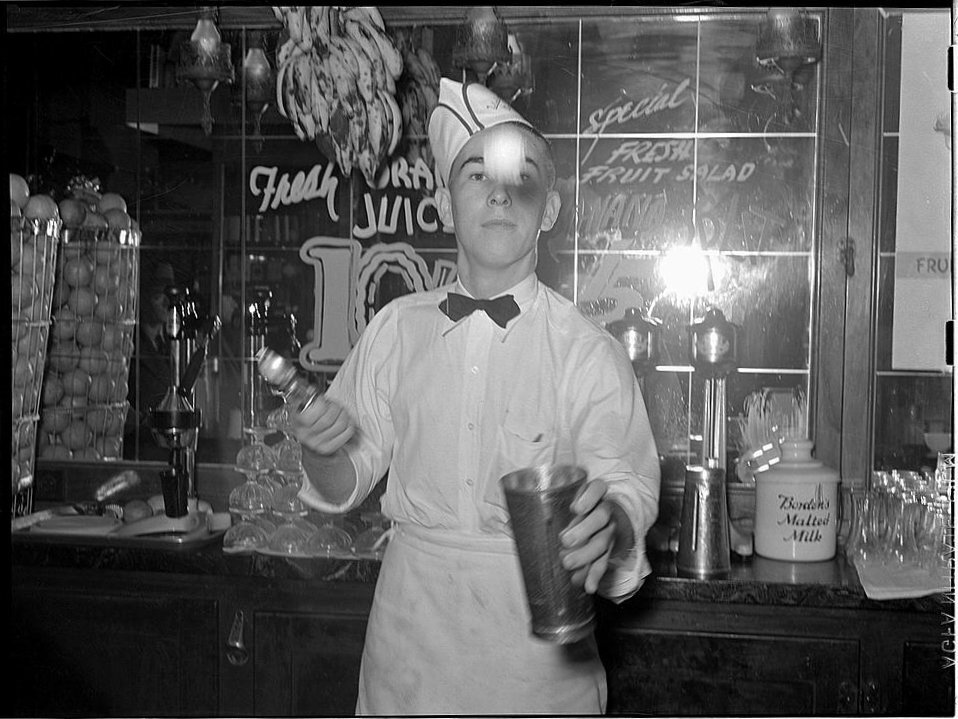

The sense of jerk meaning to dispense drinks, from the pulling motion needed to operate a beer or soda tap, also appears in the mid eighteenth century. It originally started as a term for dispensing beer, as seen in this article with a dateline of 17 February 1868. Here frail means morally weak, subject to temptation:

After the successful raids on the gamblers, the “beer jerkers” cam in for their share of persecution, and for a time the frail priestess of Bacchus seemed extinguished. But Molly Fitzgerald and Co. have instituted a new firm with new goods, and opened a beer-jerking saloon on Fourth street. The officers promptly made arrests, and continued to do so. Molly, who is Queen of the beer-jerks, had the officers arrested for assault. The jury fined them each $100 and costs. And yesterday a highly intelligent jury decided that Molly Fitzgerald & Co. owned the saloon, and had the right to jerk beer to their heart’s desire. If this decision be sustained we will soon be again cursed with beer-jerking saloons that will be the resorts of thieves and the lowest grades of frail women.

But by the 1880s the verb to jerk was being used to refer to dispensing soft drinks. From the 1883 The Grocery Man and Peck’s Bad Boy, in which the bad boy of the title says:

Well, I must go down to the sweetened wind factory, and jerk soda.

And a bit later on in a conversation with the grocery man:

Well, I have quit jerking soda.

“No you don’t tell me,” said the grocery man as he moved the box of raisins out of reach.” You’ll never amout [sic] to anything unless you stick to one trade or profession. A rolling hen never catches the early angleworm.”

“O, but I am all right now. In the soda water business, there’s no chance for genius to rise unless the soda fountain explodes. It is all wind, and one gets tired of the constant fizz. He feels that he is a fraud, and when he puts a little syrup in a tumbler, and fires a little, sweetened wind and water in it until the soap suds fills the tumbler, and charges ten cents for that which only costs a cent, a sensitive soda jerker, who has reformed, feels that it is worse than three card monte.

That’s how a medieval shoemaking jargon term came to mean a server of beverages, an unpleasant person, or an act of masturbation.

Sources:

“From St. Louis” (17 February 1868). Davenport Gazette (Iowa), 22 February 1868, 1. NewspaperArchive.com.

Green’s Dictionary of Slang, 2021, s.v. jerk off, v., jerk, n.1.

Middle English Dictionary, 2019, s.v. yerkid, ppl.

Oxford English Dictionary, third edition, June 2019, s.v. yark, v.2, jerk, v.1, jerking, n.1, jerk, n.1 and adj.2, jerk-off, n. and adj.

Parsons, Robert. An Epistle of the Persecution of Catholickes in Englande. G.T., trans. Rouen: Fr. Parson’s Press, 1582, 124. Early English Books Online (EEBO).

Peck, George W. The Grocery Man and Peck’s Bad Boy (Peck’s Bad Boy, No. 2). Chicago: Belford, Clarke & Co., 1883, 126, 136–37. HathiTrust Digital Archive.

Perelman, S. J. “Letter to I. J. Kapstein” (1 March 1937). Don’t Tread on Me: The Selected Letters of S. J. Perelman. Prudence Crowther, ed. New York: Viking, 1987, 11. HathiTrust Digital Archive.

Pollock, Albin J. The Underworld Speaks. San Francisco: Prevent Crime Bureau, 1935. HathiTrust Digital Archive.

Werdmüller, Otto. A Spyrytuall and Moost Precyouse Pearle. London: S. Mierdman for Gwalter Lynne, 1550, fol. 13v. Early English Books Online (EEBO).

York Memorandum Book, part 1 of 3. Publications of the Surtees Society, 120. York: Andrews and Co., 1912, 194. HathiTrust Digital Archive.

Photo credit: Russell Lee, February 1939, Library of Congress. U.S. government photo, public domain image.