18 January 2021

One of the pleasures of researching the origin or words is reading texts written in days past that reflect a very different sensibility than that which we have today. Such is the case with the origin of hooky or hookey, meaning truancy, usually found in the verbal phrase to play hooky. The nineteenth century literature is replete with lurid tales of what evils can befall children who skip school.

As to the origin of this American slang word, we don’t know for certain, but it has a likely origin in the Frisian hoeckje, meaning corner, and hoeckje spelen is to play hide-and-seek in Dutch. The word was introduced to North America through the Dutch colony of New Amsterdam, what is now New York. In his 1865 Anthology of New Netherland, Henry Murphy writes of Nicasius de Sillè, first councilor to Governor Stuyvesant of the New Netherland colony, c. 1656, saying:

It marks the simplicity of the times to read his complaints, on one occasion, to the burgomasters and schepens of the city, of the dogs making dangerous attacks upon him while performing that service, of the hallooing of the Indians in the streets, and the boys playing hoeckje, that is, playing hide and seek around the hooks or corners of the streets, to the prejudice of quiet and good order.

And a hundred years later, Robert Carse writes of the New Amsterdam colony, saying, “boys played hoeky—pranks on each other.” These are later writings, but I am sure that a Dutch speaker who delves into the original documents from the seventeenth century colony would find examples the Dutch word being used.

Fifty years ago, researcher John Sinnema suggested that hooky survived in the slang of school children, changing in meaning over the years, perhaps influenced by the sense of to hook meaning to steal, and coming to mean to play the truant. The idea is plausible, but the long gap between the Dutch colony and the term’s next recorded appearance in the mid nineteenth century somewhat militates against it.

In any case, hooky makes its way into English publication by 17 June 1842 in the pages of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle:

For it is a fact that “men are but children of a larger growth.” “When I was a child, I spake as a child,” &c., “but when I became a man, I put away childish things.”—That is, if we rightly understand the language, he no longer drove the hoop, shot marbles, flyed kites, (not even after the Wall Street fashion,) hunted birds’ nests, played “hookey,” and chased butterflies, with eyes nearly starting from their sockets with excitement, and his long, silken tresses streaming in the breeze (for it was not the custom to rob the children’s heads of their beautiful locks in those days.)

There is this March 1846 “advertisement” in the Common School Journal. I place “advertisement” in scare quotes because the item is almost certainly a joke and not a real advertisement for a teacher’s services:

ADVERTISEMENT. — Mr. Starling respecktfully caution his patterns and the publick that he is a going to teach a scool in this town in the branches of learning and the scolars will find there own books as will be well used except them that plays hookey will be licked with the strap, — 8 cuts for a big boy, and 5 cuts for a little one. For further infarmation, inquire of Mr. Prass the sope biler whose darter gut her edication as above. N. b. — Wanted a plaice to board with washing and a bed all to hisself.

EBEN STARLING, JUN. Balt. Sat. Visiter.

And John Russell Bartlett records the term in his 1848 Dictionary of Americanisms, making it clear that the term was rather common by the time it first sees print:

HOOKEY. To play hookey, is to play truant. A term used among schoolboys.

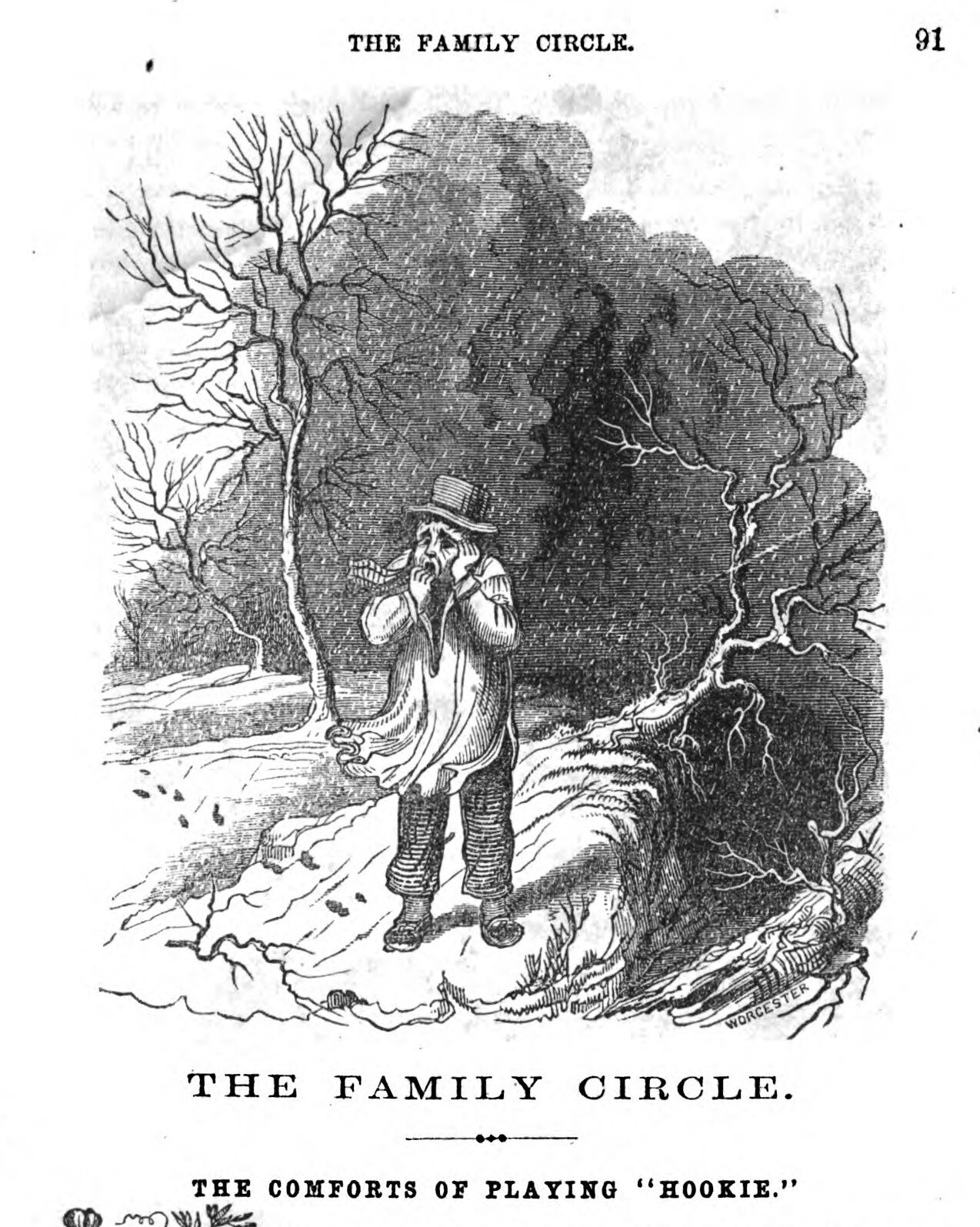

A use from an 1856 issue of Mother’s Magazine gives a slightly different definition of playing hooky, that is not coming directly home after school and instead getting into mischief. The article, titled “The Comforts of Playing Hookie,” in its opening refers to the accompanying picture of a boy lost in a snowy forest, far from home, and certain to die a horrible death on account of disobeying his mother:

Have you any sympathy with this poor boy? Do any of you see your own likeness here? Do you remember when you strayed away, after school, to have a slide, or a skating, on the pond, knowing all the while that your mother was expecting you home? Do you remember how, when it was near dark, and the snow began to fall thick and heavy, you started on your way home, half frozen, dissatisfied with yourself, and ready to cry with vexation, without finding anybody to be vexed with but yourself? Then you began to wish you had gone directly home from school

The difference in meaning may be the result of the slang term being used in slightly different ways by different communities, or perhaps the adult author and editors did not quite understand the children’s slang term.

One more lurid tale before we leave it. An 1868 tale by Mary Prescott tells of young Tommy, who skips school, falls in with a bad lot, gets arrested for fighting, and narrowly escapes having to tell his mother when another woman, mistaking him for her own son, rescues him from jail:

But if there are obstacles in the way of being a good boy, he soon found that to be a bad boy was not to live in clover; for he was hardly a rod from the door when his mother called out that he had forgotten his satchel, and he must needs go back for it! What did a boy who was going to play truant want of a satchel? But still he had to drag it along with him all the same.

By and by he fell in with some other schoolboys, some of whom had had permission to stay away, while others, like himself, were taking it. This encouraged Tommy mightily. I'm not certain but he would have ended by going to school, after all, if he hadn't fallen in with them.

“Brought your satchel along,” said one of them; “what a greeny you are, Tommy ' If the master should happen to see you, he'd know in a minute that you were playing hooky.”

The story continues with Tommy, falling under the bad influence of the other boys, being arrested before eventually being returned to the loving embrace of his mother, narrowly avoiding going down the path to a life of crime. Such is what can befall the truant, at least in the imaginings of nineteenth-century parents and editors.

In any case, by the second half of the nineteenth century, hooky was a well established term in the vocabulary of both children and adults.

Sources:

Bartlett, John Russell. Dictionary of Americanisms. New York: Bartlett and Welford, 1848, 180. HathiTrust Digital Library.

“Public Amusements.” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 17 June 1842, 2. Brooklyn Public Library: Brooklyn Newsstand.

Carse, Robert. Ports of Call. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1967, 149. HathiTrust Digital Library.

“The Comforts of Playing ‘Hookie.’” The Mother’s Magazine, 25.3, 1856, 91. HathiTrust Digital Library.

The Common School Journal, 8.5, 3 March 1846, 76. HathiTrust Digital Library.

Green’s Dictionary of Slang, 2020, s.v. hooky, n.3, play hooky, v.

Murphy, Henry C. Anthology of New Netherland. New York: Bradford Club, 1865. 188. HathiTrust Digital Library.

Oxford English Dictionary, second edition, 1989, s.v. hookey, n.

Prescott, Mary N. “Playing Truant.” Our Boys and Girls, 4.80, 11 July 1868, 440–41. HathiTrust Digital Library.

Sinnema, John R. “The Dutch Origin of Play Hookey.” American Speech, 45.3/4, Autumn–Winter 1970, 205–209. JSTOR.