27 November 2023

At least two different legions of fans misassign credit for the coinage of the phrase there ain’t no such thing as a free lunch. The first are science fiction aficionados who falsely credit Robert Heinlein for coining the phrase and its acronymic child, TANSTAAFL. The second are devotees of economist Milton Friedman, who published a 1975 collection of essays using the phrase as its title. Neither Heinlein nor Friedman originated the catchphrase or its acronym, although both undoubtedly helped popularize them.

Instead, the phrase arose out of debates between capitalists and socialists in America at the turn of the twentieth century.

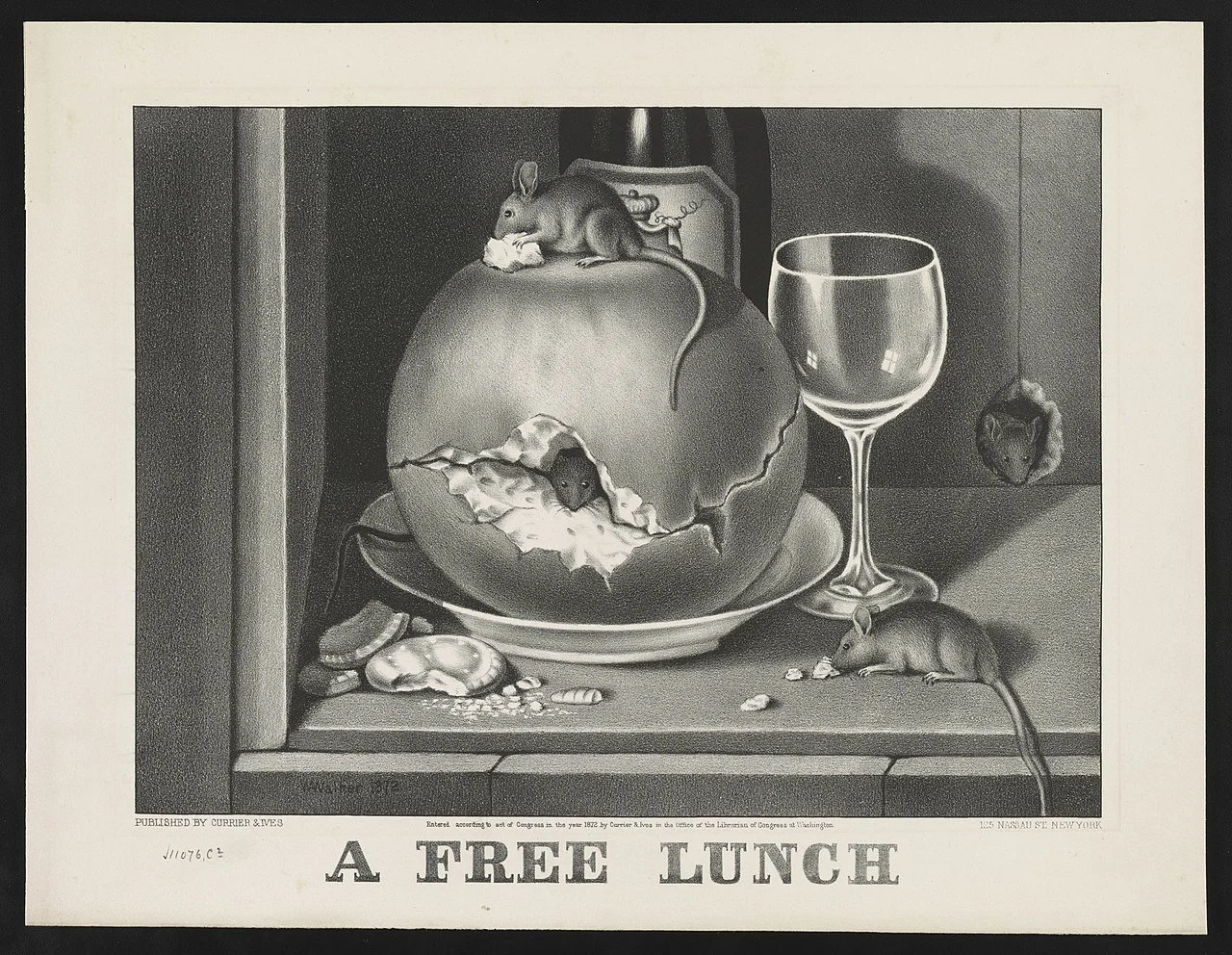

The literal free lunch is the practice of saloons offering free food to attract customers. The marketing ploy took hold and became ubiquitous in the United States in the mid nineteenth century. The earliest reference I have found to an establishment offering a “free lunch” appears in an ad in the Illinois State Register on 3 February 1840 (and on the same page is a summary of a speech by Abraham Lincoln given in the Illinois House of Representatives, a fact that is irrelevant to the history of the phrase, but is an example of the tidbits one turns up when doing research of this nature):

N. B.—Free Lunch set every day, at 11 o’clock, A. M, Hot Coffee at all hours.

By the century’s end, free lunch had entered the realms of politics and economics, becoming equated with socialism and the labor movement. There is this piece on labor negotiations between the New York Tribune and Typographical Union Local #6 that appeared in the Yonkers Herald on 26 July 1892. It uses free lunch ranter to describe a pro-union politician:

The action of a political party, which action is inseparable from this discussion, clearly shows that somebody has been trying to make fools of organized workingmen. Chauncy M. Depew, president of that corporation which is so friendly (?) to labor organizations, and a leader in Mr. Reid’s party, says: “Mr. Reid is the labor candidate. His nomination was practically made by the Typographical union.” This is only the mouthing of a free lunch ranter and clearly misrepresents the attitude of No. 6; but the union put itself in a position to be made the byword and boast of political shysters and capitalistic clowns.

Later than year, we start see precursors to the catchphrase appearing. There is this one that questions whether there is such as thing as a free lunch. But here the meaning is quite literal, referring to the presence or absence of the saloonkeepers’ practice, and not questioning whether or not the food is truly provided at no cost. Originally printed in the San Francisco Examiner on 25 September 1897, the piece was reprinted widely across the United States in the following weeks:

With bread selling at three loaves for a dollar at Dawson City, the question whether there is such a thing as a free-lunch route up there becomes one of almost international importance.

Months later we see the exact phrasing there is no such thing as a free lunch in Illinois’s Rockford Daily Register-Gazette of 24 December 1897. Here the phrase is occupying a middle ground between the literal sense of gratis bar food and the metaphorical economic sense. Mr. Pricket is literally referring to the food coming at no cost to the customer, but he is couching the literal observation in the context of a larger economic argument:

Edward L. Pricket of Edwardsville, Ills., late United States consul to Kehl, Germany, was here recently on his way home. He spoke freely and in an interesting manner of his experiences abroad. He said: “There is no such thing as a free lunch in all Europe. In fact nothing is free there. Even in Germany you have pay for your pretzels, and they do not even give a match gratuitously. I went to Europe a free trader. I return a protectionist.”

And there is this use of the phrase in the Washington Herald of 2 November 1909, which is entirely figurative:

Mr. Tillman’s idea that free lunch is good enough for anybody—or even Presidents—may appear sound to some people, but, as a matter of fact, there is no such thing as a free lunch. Somebody has to pay for it.

The phrase, with is no replaced by ain’t no, is used as the punchline of an economist’s joke in Texas’s El Paso Herald Post of 27 June 1938. The piece was originally anonymous, but the writer was later identified as columnist Walter Morrow. The joke tells of a king who asks his economic advisors to summarize the wisdom of their field for him. Economist after economist fails at the task, unable to do so without using volumes of texts and charts. The king has them summarily executed, one after another. Finally, only one economist is left, who says:

“Your majesty, I have reduced this subject of economics to a single sentence, so brief and so easily remembered that it was not necessary to put it on paper. Yet will I wager my head that you will find my text a true one, and not to be disputed.”

“Speak on,” cried the king, and the palace guards leveled their crossbows. But the old economist rose fearlessly to his feet, stood face to face with the king, and said:

“Sire, in eight words I will reveal to you all the wisdom that I have distilled through all these years from all the writings of all the economists who once practiced their science in you kingdom. Here is my text:

“There ain’t no such thing as free lunch.”

Morrow may or may not have originated the joke, but he was the first to put it in print.

The phrase also appears in a book review published in the Columbia Law Review of September 1945. By this date the catchphrase has clearly become a buzzword of the political right:

Dr. Skilton apparently expects and welcomes more intrusion of government both to regulate mortgage loans and provide money for them. […] One can obviate that by government loans at arbitrarily lows rates, but this simply means the taxpayers are asked to subsidize one group in the population. Dr. Skilton might recall this profound economic truth, “There ain’t no such thing as a free lunch.” Government has nothing to give anybody. What it gives to one man it must take from another.

Economic satire is also the origin of the phrase’s acronym, TANSTAAFL. The acronym first appears, as far as I can tell, in a 35-page, 1949 satirical, anti-Communist pamphlet titled TANSTAAFL: A Plan for A New Economic World Order, written by a Pierre Dos Utt and published by Cairo Publications of Canton, Ohio. Both the writer and publisher are fictional entities. The pamphlet using obfuscatory equations and charts as “evidence,” proposes what it says is the optimal world political and economic order, an order that in many ways resembles the Soviet Union under Stalin or Orwell’s Big Brother. The pamphlet concludes with a version of Morrow’s economics joke:

The name “TANSTAAFL” is derived from the ancient language of the Babylonians It is the subject of an old Sumerian fable. The story runs something like this:

In the days of Nebuchadrezzar a great depression settled over the valley of the Euphrates very much like the one our country experienced back in 1932.

[…]

Quaking with fear the little bald-headed man fell face down upon the floor, and sobbed:

“Most venerable King, Protector of all Babylonia, Wisest of all men—I have but one piece of advice to give. In my humble opinion,

There Ain’t No Such Thing As A Free Lunch”

Science fiction writer Robert Heinlein doesn’t enter into the history of the phrase until some seventeen years later, with the serialized publication of his novel The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress in the magazine Worlds of IF in February 1966. The novel depicts a libertarian political revolution in a lunar colony. Heinlein, an ardent libertarian, undoubtedly had encountered the phrase and its acronym elsewhere and incorporated them into his book:

“Gospodin,” he said presently, “you used an odd word earlier—odd to me, I mean.”

“Call me ‘Mannie’ now that kids are gone. What word?”

“It was when you insisted that the, uh, young lady, Tish—that Tish must pay too. ‘Tone-stapple,’ or something like it.”

“Oh, ‘tanstaafl.’ Means ‘There ain’t no such thing as a free lunch.’ And isn’t,” I added, pointing to a FREE LUNCH sign across room, “or these drinks would cost half as much.”

Friedman enters the picture a decade later with his book of that title.

So that’s how a marketing ploy by nineteenth century saloonkeepers became an anti-socialist catchphrase.

Sources:

Dos Utt, Pierre. TANSTAAFL: A Plan for a New Economic World Order. Canton, Ohio: Cairo Publications, 1949.

Felts, David V. “Second Thoughts.” Decatur Herald (Illinois), 23 September 1949, 6/3. Newspapers.com.

Hanna John. “Government and the Mortgage Debtor (1929 to 1939) by Robert H. Skilton” (review). Columbia Law Review, 45.5, September 1945, 803–05 at 805. JSTOR.

Heinlein, Robert A. “The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress.” Worlds of IF, February 1966, 108–09. Archive.org.

“Little Too Radical.” Rockford Daily Register-Gazette (Illinois), 24 December 1897, 11/2. Readex: America’s Historical Newspapers.

Morrow, Walter. “Economics in Eight Words.” El Paso Herald Post (Texas), 27 June 1938, 4/1. Newspaper Archive.

Oxford English Dictionary, third edition, June 2008, s.v. free lunch, n.

San Francisco Examiner, 25 September 1897, 6/2. Newspapers.com.

Shapiro, Fred R. The New Yale Book of Quotations. New Haven: Yale UP, 2021, 176, 368, 576.

“Springfield Exchange Coffee-House,” Illinois State Register (Springfield), 3 February 1840, 3/1. Newspapers.com.

“The Trib and Big Six.” Yonkers Herald (New York), 26 July 1892, 3/3–4. Newspapers.com.

Washington Herald (Washington, DC), 2 November 1909, 6. Library of Congress: Chronicling America.

Image credit: Currier & Ives, 1872. Library of Congress. Public domain image.