17 May 2023

To have a field day means to triumph, to have great success at some endeavor. Field day is also a term used by schools and other organizations to denote a day devoted to athletic competition among the students and members. But these current meanings are far removed from the term’s origin in eighteenth-century military exercises.

Field day appears in the early eighteenth century, referring to military exercises or reviews, a day spent outside of the barracks. We have this from London’s Daily Journal of 3 September 1723:

Yesterday was Field Day for the Horse in Hide-Park [sic], when one of the four Troops of Guards pass'd in Review there before the several Officers of their own Corps.

About a century later, a figurative use of field day, meaning a day that is remarkable or successful, appears. The underlying metaphor would seem to equate success and celebration with flags flying and troops in brightly colored uniforms marching by. English politician Thomas Greevey wrote the following in a letter dated 26 March 1827, likening a dinner party to a military review:

Saturday was a considerable field day in Arlington Street, the Duncannons and the Jerseys, Geo. and Mrs. Lamb, Lord Foley, Punch Greville, and Genl. McDonald, and a very merry jolly dinner and evening we had. What remarkably fresh, clean looking creatures the sisters—Ladies Jersey and Duncannon are.

In 1864, journalist and publisher Charles Knight uses field day to describe 27 February 1812, a day of great speeches in the English parliament and an early-career scoop for Knight:

Thursday, the 27th of February, is to be a great field-day in the Commons. I must be there at noon, to secure a seat in the gallery. […] Up rose Mr. Canning. Somewhat alarmed I began to write. I gained confidence. His graceful sentences had no involved construction to render them difficult to follow. His impressive elocution fixed his words in my memory. Some matters I necessarily passed over; but the great point of his speech, that he was for speedily granting the Catholic claims with due safeguards, was an important one for the journal which I was suddenly called upon to represent, and I caught the spirit, if not the full words, of the declaration in which he stood opposed to the Minister, and to his own ancient rival. I ran to the office (for young legs were faster than hackney-coaches), wrote my report, to the astonishment of the regular staff of reporters, and went happy to bed at five o'clock. I doubt whether any literary success of my after-life gave me as much pleasure as this feat.

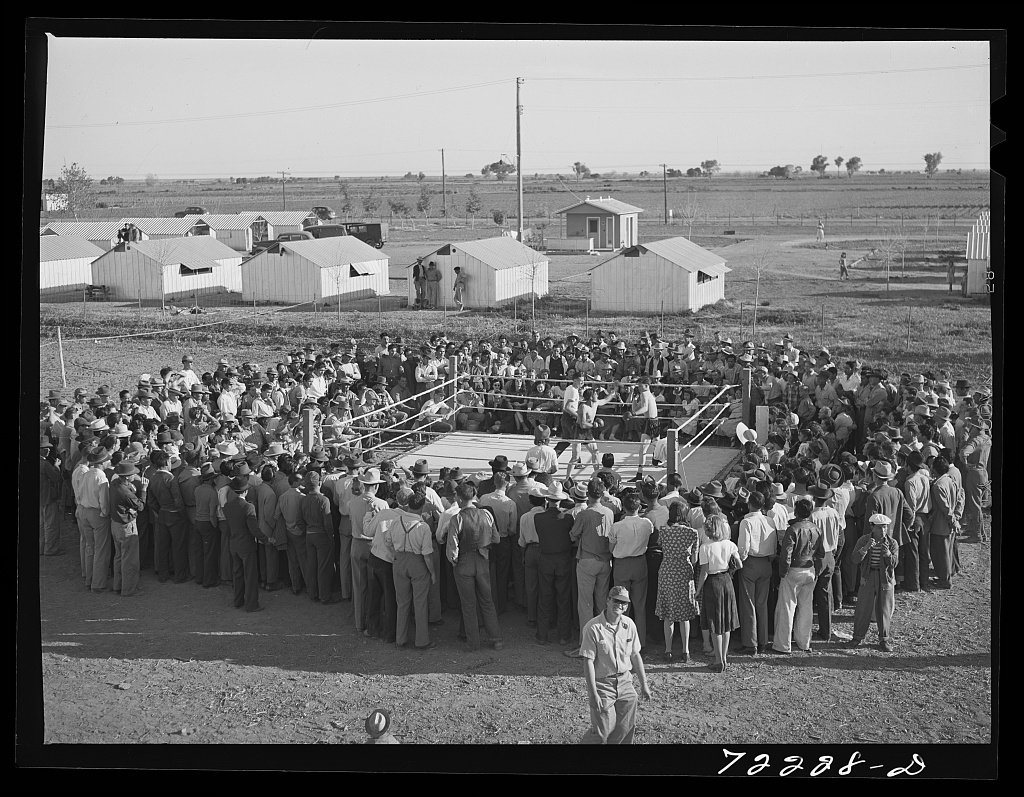

But before this figurative use of field day to refer to a success, the term was also being used in the context of sports, another extension of the original, military sense. We have this from London’s Observer of 5 March 1821 referring to a series of boxing matches:

Thus it has been seen, that the opening of the present pugilistic season has been distinguished by an activity of no common description. During the last fortnight there has been no less than three field days, on which competitors for bruizing honours of high repute have had the felicity of mashing each others [sic] frames with the most perfect good will for the two-fold purpose of amusing their enlightened patrons, and replenishing their almost exhausted finances.

And by 1856, this sense had been taken up by schools. From the sporting magazine The Field of 22 November 1856:

The undergraduate members of Pembroke College had a grand field-day on Tuesday last, on the Old Bullingdon ground, which the proprietor, Mr. Edward Hurst, had kindly placed at their disposal, and where a numerous field of spectators were much gratified at the agility and prowess exhibited in the various athletic sports which formed the afternoon’s amusements.

The original, military sense of field day has faded from use, except when referring to eighteenth century military maneuvers, but the general and school metaphorical uses live on.

Sources:

Creevey, Thomas. Letter (26 March 1827). In John Gore, ed. Creevey’s Life and Times. New York: E.P. Dutton, 1934, 236. HathiTrust Digital Archive.

The Daily Journal (London), 3 September 1723, 2/1. Gale Primary Sources: Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century Burney Newspapers Collection.

Knight, Charles. Passages of a Working Life, vol. 1 of 3. London: Bradbury & Evans, 1864, 1.109–11. HathiTrust Digital Archive.

Oxford English Dictionary, third edition, June 2011, s.v. field day, n.

“Pastimes.” The Field (Bath, England), 22 November 1856, 328/4. ProQuest Magazines.

“Pugilism.” The Observer (London), 5 March 1821, 1/3. Newspapers.com.

Photo credit: Russell Lee, 1942, US Farm Security Administration/Office of War Information. Library of Congress. Public domain image.