9 November 2022

[14 November 2022: added the final sentence for clarification]

For many, if not most, calculus is associated with suffering, whether it be suffering through a math class or passing a kidney stone. The word calculus comes from Latin, where it means stone, either a pebble or a hard accretion that forms in the body. Calculus is a diminutive of calx, literally meaning “little stone.” That explains why calculus is a medical term for a kidney stone, but where does the mathematical sense come from?

You’ve probably guessed the correct answer. It comes from calculations using stone counters or abaci.

English use of calculus to mean a small, hard object, be it formed geologically or biologically, dates to Middle English. John Trevisa uses it in his translation of Bartholomæus Anglicus’s De proprietatibus rerum (On the Properties of Things), which was completed sometime before 1398:

Calculus is a litel stoon ymedled with erthe and is round and most hard and pure and most smoþe and playn in euerich syde, and haþ þat name calculus for it is ytrodden with feet wiþoute gref of his smeþenesse and playnnes. And contrarie herto is a litel stoon þat hatte scrupulous “cheselle” and is most rough and scharpe and ful light. If it falleþ betwene a mannes foot and þe schoo it grieueth ful sore. And no such stones þat [ben] scharpe and harde ben cleped scrupea, as Isider seiþ libro xvi. Capitulo iii. And ofte in the body of a beste þis stoon bredeþ of hoote humours and glemy, now in þe bleddre and now in þe reynes, as Costantyn seiþ. Loke byfore libro vii. De passionibus renum.

(Calculus is a little stone mixed with earth and is round and very hard and pure and very smooth and plain on all sides, and has the name calculus for it is trod upon by feet without injury because of its smoothness and plainness. And in contrast to it is a little stone that is called scrupulous “cheselle” and is very rough and sharp and very light. If it falls between a man’s foot and the shoe it hurts very sorely. And no such stones that are sharp and hard are called scrupea, according to Isidore, book 16, chapter 3. And often in the body of a beast this stone grows from hot and viscous humors, sometimes in the bladder and sometimes in the kidneys, according to Constantine [the African]. Look in book 7 of About Diseases of the Kidneys.)

Both scrupulous (Latin) and cheselle or chesil (English) mean small, sharp pebbles or gravel, such as those found on some beaches. The English word comes from the Latin cisellum, a diminutive of caesum (cutting), which is also the root of chisel and scissors.

The mathematical sense of calculus starts to develop in the mid seventeenth century. It is first used to refer to stones or counters used for counting. We see this use in Charles Hoole’s 1649 Latin textbook, although he uses it as a Latin, not an English, word:

a counter, Calculus, li. m.

ship-counters, or counters to cast account with, Abaculi.

But a dozen years later it is recorded as an English word in Thomas Blount’s 1661 Glossographia, a dictionary of “hard words”:

Calcule (calculus) and account or reckoning; a Table-man, Chess-man, or Counter to cast accounts withal.

And by the end of the seventeenth century, calculus is being used to mean a method of calculation. From John Arbuthnot’s 1692 Of the Laws of Chance:

The Calculus of the preceeding Problems is left out by Mons. Hugens, on purpose that the ingenious Reader may have the satisfaction of applying the former Method himself; it is in most of them more laborious than difficult.

And the specific terms differential calculus and integral calculus are in place by first half of the eighteenth century. These are not direct developments within English, but rather calques of French and German to describe the work of Leibniz.

Sources:

Arbuthnot, John. Of the Laws of Chance. London: Benjamin Motte, 1692, 48. Early English Books Online (EEBO).

Blount, Thomas. Glossographia, or, a Dictionary Interpreting All Such Hard Words of Whatsoever Language Now Used in Our Refined English Tongue. London: Thomas Newcombe for George Sawbridge, 1661, s.v. calcule. Early English Books Online (EEBO).

Hoole, Charles. An Easie Entrance to the Latine Tongue. London: William Dugard for Joshua Kirton, 1649, 309. Early English Books Online (EEBO).

Lewis, Charlton T. and Charles Short. A Latin Dictionary. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1879, s.v. calculus, n. Brepols: Database of Latin Dictionaries.

Middle English Dictionary, 2019, s.v. calculus, n.

Oxford English Dictionary, second edition, 1989, s.v. calculus, n., integral, adj. and n.; third edition, March 2016, s.v. differential, adj. and n.

Trevisa, John. On the Properties of Things: John Trevisa’s Translation of Bartholomæus Anglicus De Proprietatibus Rerum, vol. 2 of 3. Oxford: Clarendon Press: 1975, 16.20, 837–38.

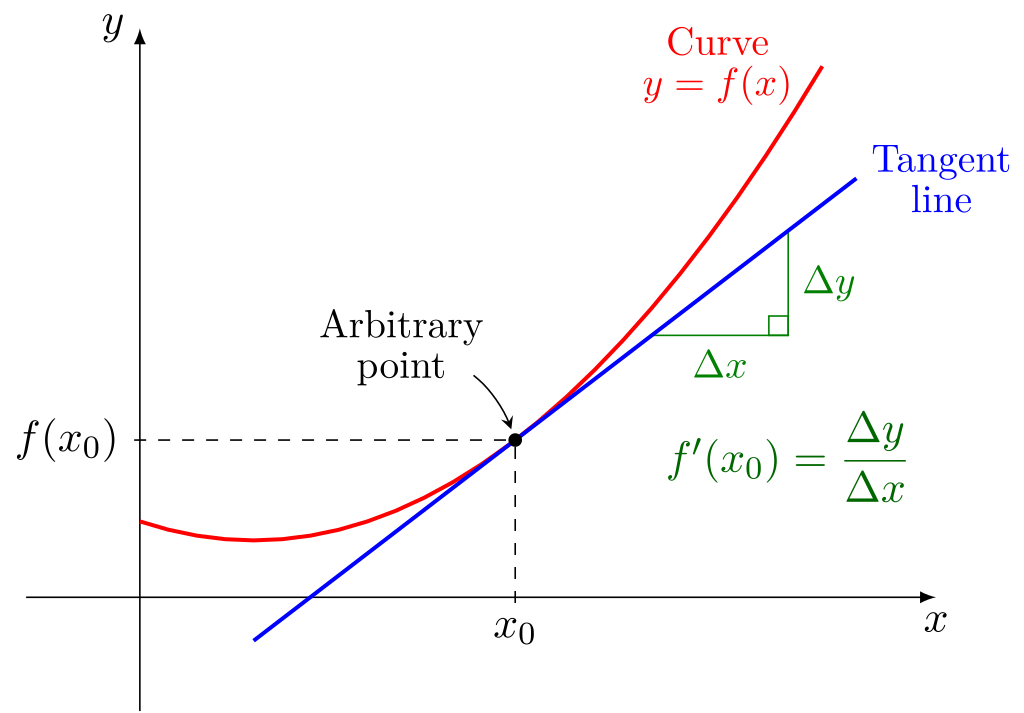

Image credit: Cristian Quinzacara, 2021. Wikimedia Commons. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.