23 May 2020 (correction, 24 May)

In present-day parlance, bimbo is usually used to refer to an attractive, but unintelligent, woman, but it did not always mean this. The story of bimbo leads us through the worlds of criminals, racism and xenophobia, and gay sub-culture. It also appears to be a word that was borrowed from Italian multiple times in the early twentieth century, acquiring a different meaning for each group and sub-culture that borrowed it.

Bimbo is from the Italian word meaning baby, akin to bambino. It makes a number of appearances in English as a proper name in the opening years of the twentieth century. Searching turn-of-the-century newspapers turns up uses as the names of various animals: several pet dogs, a racehorse named Lady Bimbo, and a monkey. It was the name of a vaudeville comedy-acrobat act, and it was the name of an “Italian” hotel in San Francisco that appears as a crime scene in multiple news stories.

In what may be either a serious news story or a satire (from the remove of over a century, it’s hard to tell how much is fact and how much is fiction), Bimbo appears as the name of a “gypsy” a series of stories in Chicago’s Day Book about a certain George Bimbo, such as this one from 18 November 1913:

Love among they gypsies has given the police of the Maxwell street station more trouble. The case of George Bimbo and his purchased gypsy princess, Mary Mitchell, bids fair to end in tragedy unless the courts intervene. [...] Two of Bimbo’s loyal supporters have been Stephan George and Yanks Dureck. This morning they were found at the corner of 12th street and Racine avenue. They had been attacked and beaten by four men. Meanwhile the younger element of the tribe is planning to dethrone “King” Mitchell and make Bimbo kind of the nomads—if he can be found.

From these names and stories such as this, bimbo developed its first slang sense of a thug or tough guy, a sense laced with racial and ethnic implications. In another story, this time no mistaking it as anything but a satire, in the Washington Herald on 1 February 1914, the writer uses the name clearly expected the audience to connect the name with the sense of a thug:

A feud between Jacob Bimbo and Jacob Inski, sugar dealers, was settled today by Judge Dingbats in an unusual way. Bimbo was haled into court to answer to a charge of assault and battery on complaint of Inski. It developed that Bimbo had attacked Inski, his business rival, striking him in the face and kicking him in the stomach.

At about the same time, a second sense of bimbo developed in English, that of an insignificant or worthless person, a fool, or a dupe. There is this July 1919 story possibly by Damon Runyon in which some tough guys use bimbo to mean a man who isn’t one. (Green’s Dictionary of Slang credits the writer, but the Richmond Times-Dispatch version that I have access to has no byline.) I include the story in full because the full context is necessary to understand it and because it also involves cartoonist Thomas A. “Tad” Dorgan, who features in many origins of early twentieth century slang terms:

PEST ACCORDED BEATING

Yankee Schwartz Thrashes “Bimbo” Who First Challenges “Tad” Dorgan

TOLEDO, O., July 2.—A pest was operating in the lobby of the Secor last night. He challenged “Tad” Dorgan to battle. “Tad” was busy, so Yankee Schwartz, the old Philadelphia boxer, took charge of the case for him.

Everybody went out into the street in front of the Secor, and for twenty minutes there was as sweet a setto as you’d want to see. Schwartz finally got home in front. “No bimbo can lick me,” said he, breathlessly, at the finish. “What’s a bimbo?” somebody asked “Tiny” Maxwell, on the assumption that “Tiny” ought to be familiar with the Philadelphia lingo.

“A bimbo,” said Tiny, “is t-t-two degrees lower than a coo-coo-cootie.”

“Tiny” Maxwell, who was anything but, was a former football player, coach, referee, and sportswriter. He had a stutter.

Paradoxically, or perhaps not, this same sense also arises about this time in Polari. Polari was a cant used by British gay men and lesbians in the twentieth century until around 1970, when its use went into sharp decline. This use in Polari probably comes from the Italian via the Mediterranean Lingua Franca that was used by sailors into the nineteenth century, which would make it a parallel development to this particular American slang sense.

Bimbo seems to have been borrowed again sometime before 1920, where it came to mean an attractive person, a natural extension of the sense of baby. But it could be used either to refer to a man or to a woman. For instance, there is this from the Washington Times of 21 August 1922 in a column discussing a man who pretended to be a European prince in order to seduce women:

Women Be Warned and learn about men from him.

With Europe all mussed up, it’s going to be a cinch for bimbos from abroad to spill smooth social etiquette and hypnotize unsuspecting romantic damsels into matrimony. Better to gaze with favor upon some bashful American who may not be so oo-la-la when it comes to flash affection, but is a straight shooter and an honest breadwinner.

If a bimbo born right here can put over parody like that, look out girls for the baby who blows in from the other side and gets crusty with a crest ring he may have bought off some dealer in antiques.

Note that both bimbo and baby are used synonymously here. And while the article carries a note of racism and xenophobia—with Southern Europe being implied with the use of bimbo—it also uses the term to refer to Americans, who are presumed to be “Anglo-Saxon.”

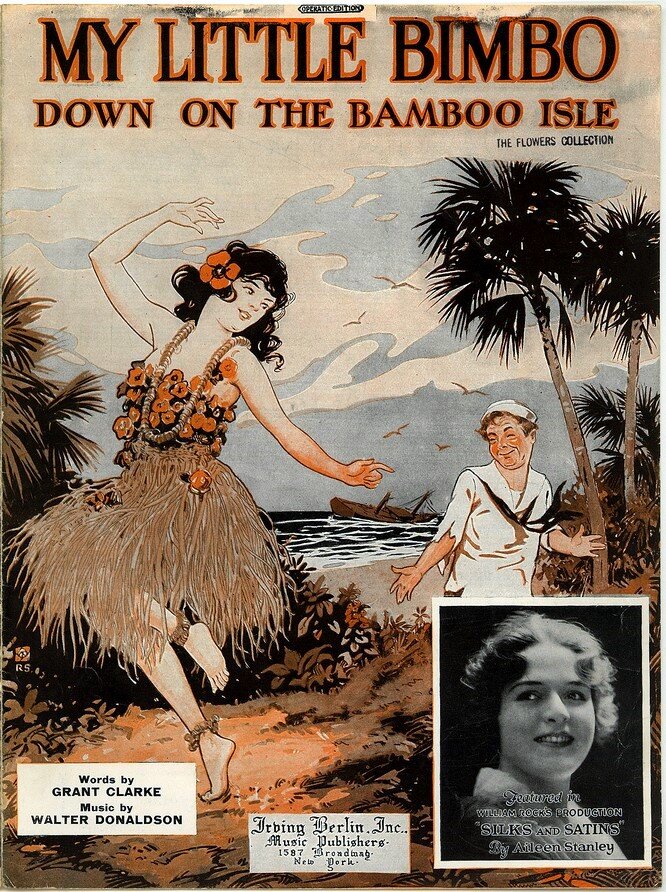

But, of course, bimbos could be female too. The song “My Little Bimbo Down on the Bamboo Isle” in the 1920 Broadway revue Silks and Satins carries much of the same xenophobia and racism, but with the genders of the seducer and the seduced being reversed:

Sailor Bill McCoy, was a daring sailor boy,

His ship got wreck’d awhile, on a Fee-jee-ee-jee Isle

He led a savage life, and hunted with a knife,

He said I’ll tell you about it don’t tell my wife.I’ve got a bimbo down on the Bamboo Isle

She’s waiting there for me Beneath a bamboo tree

Believe me she’s got the other bimbos beat a mile[...]

But by heck there never was a wreck like the wreck she made of me

For all she wore was a great big Zulu smile

My little bimbo down on the Bamboo Isle.

Again, we have a foreigner, a woman this time, dark-skinned and sexually alluring, naked except for her “Zulu smile.” Here it is the female bimbo who is stealing the innocent, white man away from his wife. The racism is palpable.

By the late-1920s the word had acquired the sense of an unintelligent woman. Walter Winchell notes this in November 1927 when writing about Variety writer Jack Conway:

Among Conway’s more famous expressions are “Bimbo” (for a dumb girl).

(I cannot, however, find any examples of Conway using the term bimbo in his writing.)

This sense of a woman who is attractive, sexually available, and stupid has largely driven out the other senses, although you can still find the term applied to men, where it has been generally more positive, although increasingly it connotes a young, attractive man who is also none too bright. As Kathy Lette wrote in her 1992 satire of Hollywood The Llama Parlour:

I was busy doing all this, when Pierce made his late, head-turning entrance. He tacked across the room, berthing briefly at various tables to ad-lib rehearsed quips and kiss the cheeks of the BBBs (the Blond, the Bronzed, and the Beautiful. Of both sexes. Believe me, living in LA you come to realise that the word “bimbo” is not gender-specific.)

Correction: a previous version said that bimbo was a clipping of bambino, which implied the clipping happened in English.

Sources:

Baker, Paul. Polari—The Lost Language of Gay Men. Routledge, 2002, 165.

Bangs, John Kendrick. “The Genial Idiot.” Washington Herald (DC), 1 Feb 1914, 26.

Clarke, Grant (lyrics) and Walter Donaldson (music). “My Little Bimbo Down on the Bamboo Isle” Irving Berlin, Inc. Music Publishers, 1920. Lester S. Levy Sheet Music Collection, Johns Hopkins Sheridan Libraries and University Museums.

Green’s Dictionary of Slang, 2020, s.v. bimbo, n.

King, Fay. “Warns Girls Against Smooth Talkers With Titles.” Washington Times, 21 August 1922, 4.

Oxford English Dictionary, second edition 1989, with June 2004 draft additions, s.v. bimbo, n.2.

Runyan, Damon. “Pest Accorded Beating.” Richmond Times-Dispatch, 3 July 1919, 8.

“War in the Gypsy Camp—All Over a Love Affair.” The Day Book (Chicago), 18 November 1913.

Winchell, Walter. “A Primer of Broadway Slang.” Vanity Fair, 1 November 1927, 67.