11 January 2024

In case you didn’t know, I not only do words and historical linguistics, I’m also an amateur astrophotographer; that is, I take pictures of the night sky. I’ve been doing it, off and on, since 2008. This is a compilation of the images I’ve taken during the past year.

I post my images to the Astrophotography section of the Wordorigins website and to Astrobin.com. If you want all the technical details (equipment used, camera settings, etc.), Astrobin is the place to find them, along with images taken by amateur astrophotographers from around the world.

All but one of these images were taken from my driveway in Princeton, New Jersey, under Bortle 6 (bright suburban) skies.

2023 was a disappointing year for my astrophotography. I was plagued by equipment failures, and there were the Canadian wildfires that mucked up the skies for most of the summer. But in looking back, I did get a baker’s dozen of decent images.

I started off the year with Comet C/2022 E3 (ZTF) on 1 February:

Comets are a challenging target to process. You need a long integration time to capture the faint tail, but during that period the comet is moving against the background stars. It’s a very different post-processing workflow than with deep sky images.

Next up was the Tadpole Nebula (NGC 1893) on 4 & 6 February. This one has a total of 7 hours, 4 minutes, and 30 seconds of integration time. It’s a false-color image using narrowband filters in the “Hubble palette” (so-called because it was invented for Hubble images), where light from Hydrogen-alpha ions is green, Oxygen-III ions are blue, and Sulfur-II ions are red. Shooting through narrowband filters like these, which only let light of a very specific wavelength to pass, allows you get details even from very light-polluted skies. But it’s only effective for emission nebulae that give off light in those wavelengths.

Bode’s Galaxy (M81) and the Cigar Galaxy (M82) is next. This one was taken over four nights from 13 February to 20 March, a total of 17 hours, 16 minutes, 30 seconds of integration time. This is a true-color (RGB) image enhanced with Hydrogen-Alpha emissions (representing star-forming regions) in red.

My image for April is something different, an image of the Sun taken through a solar telescope. Not only is the equipment different (you don’t want to point a regular telescope at the Sun), but technique for imaging the Sun and planets is different, called “lucky imaging.” Because the earth’s atmosphere creates “wobble” (what makes the stars twinkle), you take a short video and then use software to select the clearest frames, which you then stack together.

Spring is “Galaxy season” for the northern hemisphere, when we’re looking up away from the disk of the Milky Way and many galaxies are visible. I got this shot of the Sunflower Galaxy (M63) taken 11–18 May, a total of 14 hours, 25 minutes.

May also saw a supernova in the Pinwheel Galaxy (M101). It was discovered by a Japanese amateur astronomer, and I was one many who followed up with images of their own. Being able to see an exploding star in a galaxy some 20.9 million light-years from earth is pretty neat.

This next one is the only one I took from somewhere other than my driveway. This is the North America (NGC 7000) and Pelican (IC 5070) Nebulae. This one was taken on Cape Cod, Massachusetts, a relatively dark sky site (Bortle 3, if you’re counting; Princeton is Bortle 6) on 11 July. This one is only 74 minutes of integration time, but with the darker skies that was enough.

On 1–2 August, I captured the Crescent Nebula (NGC 6888). The nebula is false-color, with Hydrogen-Alpha in the red channel and Oxygen-III in the blue and green (an HOO palette). The stars are true color. Since stars are relatively bright, you don’t need long integration times and light pollution is less of a concern than for the much fainter nebulae.

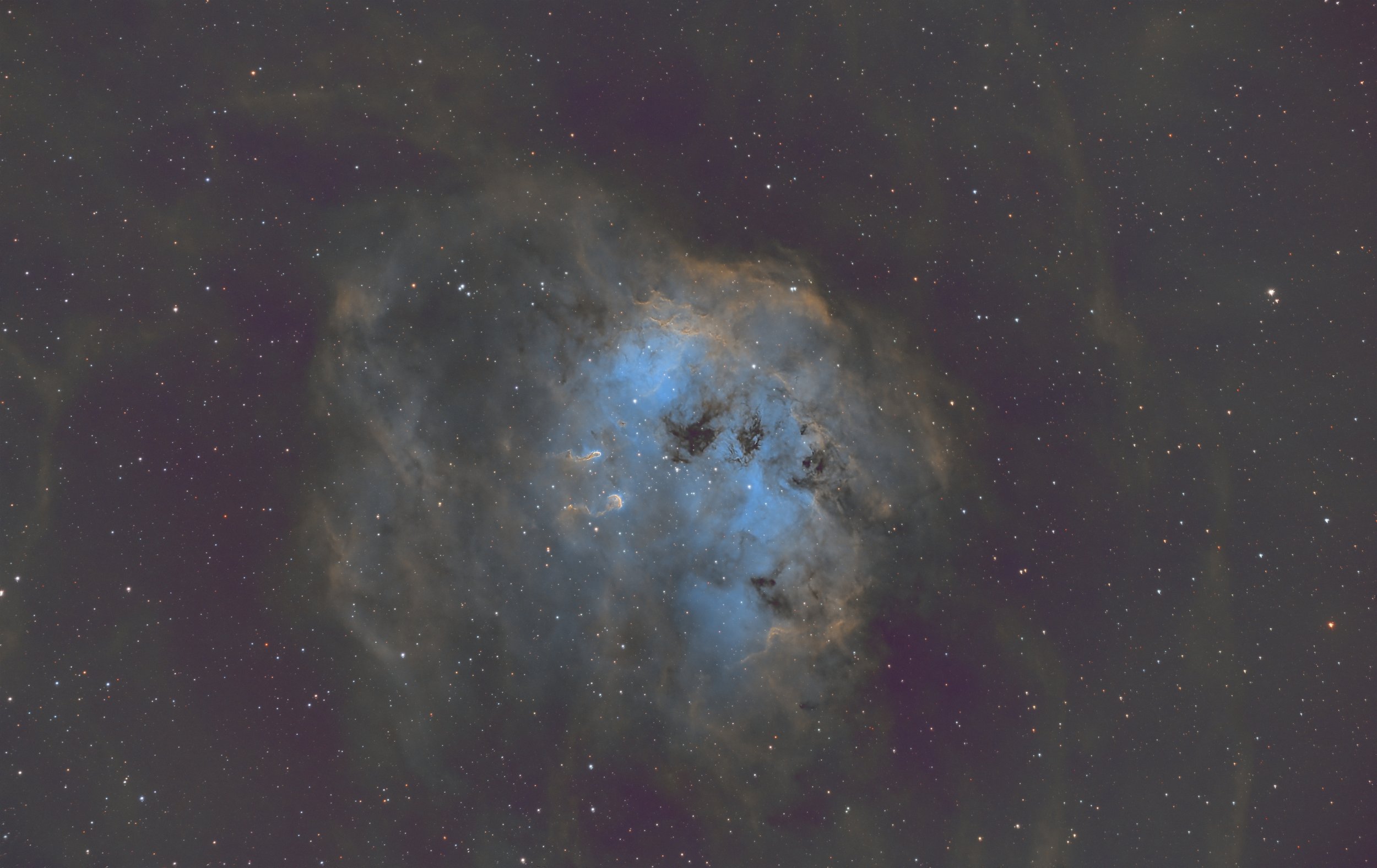

Later that month, on 19 and 20 August I captured the Wizard Nebula (NGC 7380). This one was five hours, 22 minutes total integration time. I actually got many more hours, but my telescope was knocked out of collimation (unusual for a refractor), and most of the frames were unusable. The ones I used were only saved by an AI-powered imaging processing tool, which managed to make the misshapen stars round. (The telescope has since been repaired.)

Come 1–4 October, I took this one of the Pacman Nebula (NGC 281). It’s 16 hours, 28 minutes of integration time. Again, its Hubble palette for the nebula and RGB for the stars.

On 10 and 12 October I imaged the Ghost of Cassiopeia (IC 63). This one 5 hours 20 minutes, RGB enhanced with Hydrogen-Alpha to show off the nebula.

Later that month I got a string of clear, moonless nights from 17–24 October and got this RGB image of the Pleiades (M45), a total of 23 hours, 32 minutes.

And my final image of the year was the Flaming Star Nebula (IC 405) on 1–2 November. This was another HOO image with RGB stars.

And in case you’re wondering, this is my telescope and mount, a Televue 127mm refractor on a Paramount MYT mount with a ZWO ASI2600 cooled, monochrome camera.

That is it for 2023. I only hope 2024 affords more opportunities, but the start has been inauspicious.