7 July 2022

To trip the light fantastic is to dance. This rather strange idiom is an alteration of lines from two poems by John Milton. One of these lines is in his masque Comus, first performed in 1634:

Com, knit hands, and beat the ground,

In a light fantastick round.

(A masque is a style of courtly drama popular in the Early Modern period.)

And Milton associates the light fantastic with the verb to trip in his 1645 poem L’Allegro, when he calls upon Mirth to drive away Melancholy:

Haste thee nymph, and bring with thee

Jest and youthful Jollity,

Quips and Cranks, and wanton Wiles,

Nods, and Becks, and Wreathed Smiles,

Such as hang on Hebe's cheek,

And love to live in dimple sleek;

Sport that wrincled Care derides,

And Laughter holding both his sides.

Com, and trip it as ye go

On the light fantastick toe,

And in thy right hand lead with thee,

The Mountain Nymph, sweet Liberty.

Milton apparently intended both light and fantastick to be independent of one another; the dancing toe is light, and it is fantastick. But it was read by many to be a single phrase. The adjectival phrase light fantastic, associated with dancing, appears frequently starting in the 1730s and becoming something of a cliché in the process. We see an abridged form of Milton’s line in a 1731 poem by a William Ward:

See the Belle flutter with the sprightly Beau!

They trip it on the light, fantastic Toe:

Nor Words, nor Sighs, their am’rous Thoughts impart;

They dance, and glitter at each other’s Heart!

Light fantastic most often, but not always, is found modifying toe. For instance, there is this exception from a 1730 translation of François Bruys’s The Art of Knowing Women:

With Roses crown’d, on Flow’rs supinely laid,

ANACREON next the sprightly Lyre essay’d,

In light fantastic Measures beat the Ground,

Or dealt the Mirth-inspiring Juice around.

Presumably, the idiom did not exist in Bruys’s original French.

By the beginning of the nineteenth century, the phrase had become so overused that it no longer needed a noun to modify. And by 1809 light fantastic appears as a compound noun meaning dance, as we see in this 9 February 1809 notice in London’s Morning Post:

ELLISTON is engaged for Cheltenham by WATSON: and also the Misses ADAMS, “to trip it on the light fantastic.”

One last citation. Walter Scott uses the phrase in his 1824 novel St. Ronan’s Well and includes an editorial note alongside it:

The music greatly aided them in this last purpose, and it was not long ere a dozen of couples and upwards, were “tripping it on the light fantastic toe,” (I love a phrase that is not hackneyed) to the tune of Monymusk.

One assumes that Scott’s tongue was firmly planted in cheek when he put the parenthetical comment into the mouth of his narrator.

Sources:

Bruys, François. The Art of Knowing Women: or, the Female Sex Dissected. London: 1730, 87. Eighteenth Century Collections Online (ECCO).

“Fashionable World.” Morning Post (London), 9 February 1809, 3. Gale Primary Sources: British Library Newspapers.

Milton, John. Poems of Mr. John Milton. London: Ruth Raworth for Humphrey Moseley, 1645, 31–32, 81. Early English Books Online (EEBO).

Oxford English Dictionary, third edition, December 2021, s.v. light fantastic, n.

Scott, Walter. St. Ronan’s Well, vol. 2 of 3. Edinburgh: Archibald Constable, 1824, 191–92.

Ward, William. “To the Reverend Mr. Mabell” (1731). In Mary Barber, Poems on Several Occasions. London: C. Rivington, 1735, 207. Eighteenth Century Collections Online (ECCO).

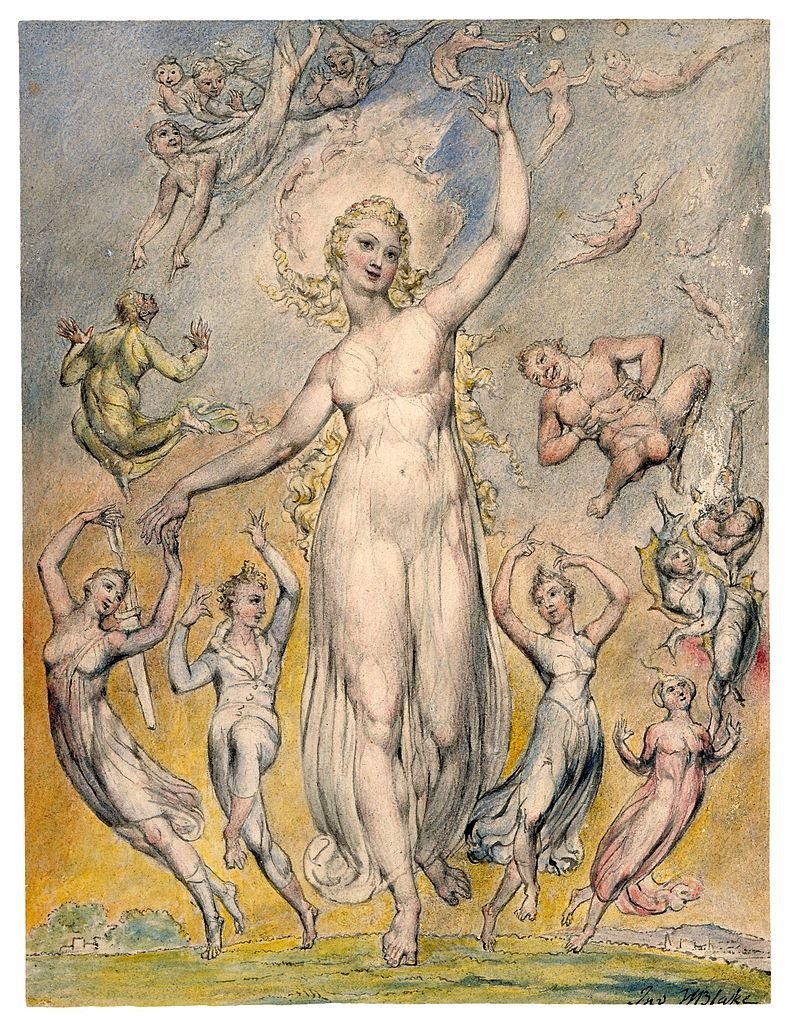

Image credit: William Blake, between 1816–20. Morgan Library. Public domain image.