22 June 2022

The word tip has multiple meanings in English. Here I am focusing on the sense of to give either a piece of information or a small sum of money—in the latter case, particularly to a servant or service worker—as well as the noun associated with that verb. The word comes out of early seventeenth-century criminal cant, which may confirm the opinions of those who object to the American practice of tipping service workers. Why those long-dead criminals choose tip to mean this is unknown. It may be due to an older sense of to tip meaning to tap or touch lightly, but any connection is tenuous and uncertain.

The word is first recorded as a verb in a number of slang and cant dictionaries. The earliest that I know of is in Samuel Rid’s 1610 Martin Mark-All, Beadle of Bridewell, which includes a cant dictionary containing corrections to an earlier, lost lexicon. The meaning of tip here is simply to give, often but not necessarily associated with money:

Chates, the Gallowes: here he mistakes both the simple word, because he so found it printed, not knowing the true orginall thereof, and also in the compound; as for Chates it should be Cheates, which word is vsed generally for things, as Tip me that Cheate, Giue me that thing: so that if you will make a word for the Gallous, you must put thereto this word Treyning, which signifies hanging; and so Treyning Cheate is as much to say, hanging things, or the Gallous, and not Chates.

And it also has this entry:

Tip a make ben Roome Coue, giue a halfepeny good Gentleman.

Elisha Coles’s 1677 dictionary includes this phrase:

Tip the cole to Adam Tiler, s. give the (stoln) money to your (running) Comrade.

The parenthetical words are in the original.

And the 1699 New Dictionary of the Canting Crew has this:

Tip, c. to give or lend; also Drink and a draught. Tip-your Lour, or Cole or I'll Mill ye, c. give me your Money or I'll kill ye. Tip the Culls a Sock, for they are sawcy, c. Knock down the Men for resisting. Tip the Cole to Adam Tiler, c. give your Pick-pocket Money presently to your running Comrade. Tip the Mish, c. give me the Shirt. Tip me a Hog, c. lend me a Shilling. Tip it all off, Drink it all off at a Draught. Don't spoil his Tip, don't baulk his Draught. A Tub of good Tip, (for Tipple) a Cask of strong Drink.

The noun, meaning a gratuity given to a servant, is in place by the mid eighteenth century. This particular subsense undoubtedly developed from the more general cant sense described above. The following letter appeared in the 29 May 1755 issue of The Connoisseur:

Dear Mr. Town,

I have been happy all this winter in having the run of a nobleman’s table, who was pleased to patronize a work of mine, and to which he allowed me the honour of prefixing his name in a dedication. We geniusses [sic] have a spirit, you know, far beyond our pockets: and (besides the extraordinary expence of new cloaths to appear decent) I assure you I have laid out every farthing, that I ever received from his lordship, in tips to his servants. After every dinner I was forced to run the gauntlet through a long line of powdered pick-pockets; and I could not but look upon it as a very ridiculous circumstance, that I should be obliged to give money to a fellow, who was dressed much finer than myself. In such a case, I am apt to consider the showy waistcoat of a foppish footman or butler out of livery, as laced down with the shillings and half-crowns of the guests. I would therefore beg of you, Mr. Town, to recommend the poor author's case to the consideration of the gentlemen of the cloth; humbly praying, that they would be pleased to let us go scot-free as well as the clergy: for though a good meal is in truth a very comfortable thing to us, it is enough to blunt the edge of our appetites, to consider that we must afterwards pay so dear for our ordinary.

I am, Sir, Yours, &c.

Jeffrey Barebones.

The writer’s sentiment is shared by many today. One can be in favor of service workers being paid a living wage without supporting the notion that the wage should come via the charity of customers rather than from the employer’s profits.

And the sense of the noun meaning a piece of information is in place a century later. The magazine The Athenӕum of 4 October 1845 has this complaint about publishers selling students the answers to their homework questions:

Xenophon’s Expedition of Cyrus: Books I. II. III. Translated literally, &c. for the use and advantage of Students.—Of such books as this, (“tip-books” as school-boys call them,) though they are generally used, we doubt the value. They may enable the boy to get easily through his lesson; but they must leave him nearly as ignorant of a language as before he commenced. It is books like this that make sound scholarship almost unknown among us.

While students may no longer refer to Cliff Notes and their ilk as tip-books (or tip-sites given we’re in the internet age), the practice is alive and well to the frustration of teachers everywhere.

Finally, the notion that tip is an acronym meaning to insure prompt service is utterly false, as we have seen. Whenever one hears an acronymic origin, one should immediately question it. Most stories of acronymic word origins are false.

Sources:

B.E. A New Dictionary of the Canting Crew. London: for W. Hawes, et al., 1699, sig. M2. Early English Books Online (EEBO).

Coles, Elisha. An English Dictionary. London: Peter Parker, 1677. Early English Books Online (EEBO).

The Connoisseur, 29 May 1755, 417. Eighteenth Century Collections Online (ECCO).

Lexicons of Early Modern English, 2021.

“Our Library Table.” The Athenӕum, 4 October 1845, 964. HathiTrust Digital Archive.

Oxford English Dictionary, second edition, 1989, s.v. tip, v.1; tip, v.4; tip, v.5; tip, n.3; tip, n.4.

Rid, Samuel. Martin Mark-All, Beadle of Bridewell. London: John Windet for John Budge and Richard Bonian, 1610, sig. E2, E4. Early English Books Online (EEBO).

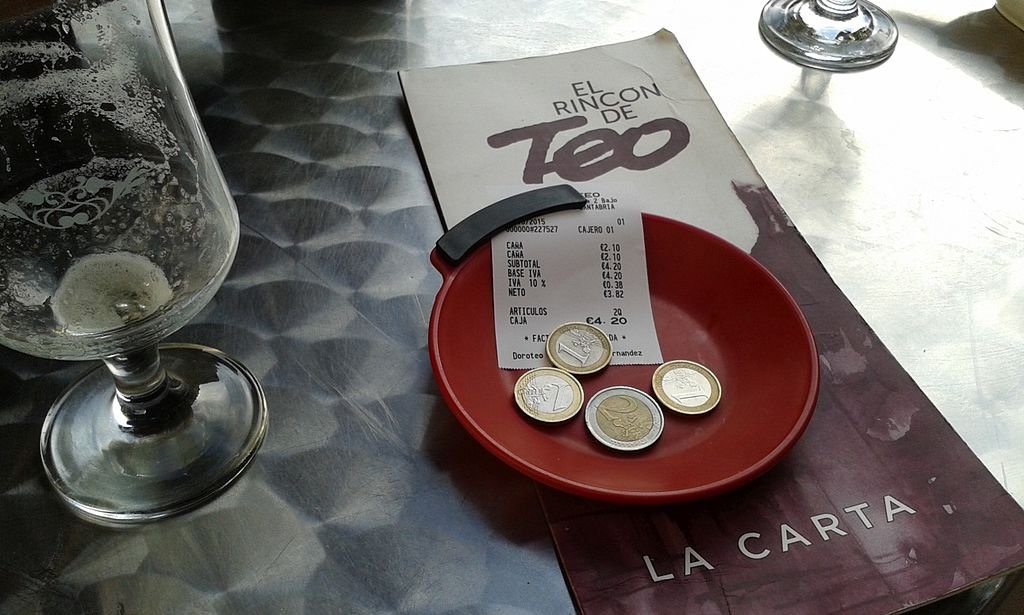

Photo credit: Adeeto, 2015. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.