5 January 2022

(Revision, 6 January: made mention of the PIE root.)

Sometimes the answer is obvious. Why are celebrities of stage, screen, sports, and other pursuits referred to as stars? Your guess is probably right.

Star has a very straightforward etymology. Our present-day word comes down to us from the Old English steorra, which in turn comes from a proto-Germanic root, and before that a Proto-Indo-European one. The Old English sense, of course, is usually that of those fiery balls of incandescent gas in the night sky (although while fairly sophisticated in astronomical matters, the people of early medieval England didn’t know what stars were made of).

An example of the Old English word can be found in Ælfric of Eynsham’s De temporibus anni, an astronomical primer penned c.998 CE. This line follows a discussion of the sun:

Eac swilce ða steorran ðe us lytle ðincað · sind swiðe brade · ac for ðam micclum fæce þe us betweonan is hi sind geðuhte urum gesihðum swiðe gehwæde.

(Likewise, the stars, which seem little to us, are very large, but because of the great distance that is between us they seem to our sight very small.)

But star could also be an appellation for a person who provides inspiration or guidance. For instance, the Virgin Mary was often dubbed Star of the Sea, or in Latin Stella maris. For instance, there is this line from an Old English hymn:

eala þu steorra sæ hal wes þu halig moder godes & mæden symble & gesælig gæt heofonan

O Stella maris, ave alma mater dei atque virgo semper et felix porta cęli.(O, you star of the sea, hail to you holy mother of God & perpetual maiden & blessed gate of heaven.)

Star began to be applied specifically to actors in the mid eighteenth century. For instance, we have the following two uses that make the metaphor explicit. From the dedication to the 1751 dramatic poem Bays in Council to the actress Esther Bland (fl. 1745–72):

That you may rise to the Summit of your Profession, that you may Shine the brightest Theatric Star, that ever enliven’d or charm’d an Audience, is the sincere Wish of,

MADAM,

Your most Obedient,

and humble Servant,

HARRY RAMBLER.

And there is this from Benjamin Victor’s 1761 History of the Theatres of London and Dublin about actor David Garrick’s rise to fame in 1741:

In the Winter Season, before the shutting up new Playhouse in Goodman’s Fields, there appeared a bright Luminary in the Theatrical Hemisphere. A young Man appeared there in the Character of Richard; and the Fame of his extraordinary Performance reached St. James’s End of the Town; when Coaches and Chariots with Coronets, soon surrounded that remote Theatre. That Luminary soon after became a Star of the first Magnitude, and was called GARRICK.

And by the opening years of the nineteenth century, we see actors referred to as stars without the metaphor being explained. From the Monthly Mirror of May 1808:

The star, however, of this company is Mr. Bradbury. His person, judgment, and genius, in the part of Athelwold, are remarkably effective, but powerful as he is in a ballet of action, his clownery, in the new pantomime of the Farmer’s Boy, is certainly more extraordinary.

At around the same time, athletes also start to be dubbed stars. From Jackson’s Oxford Journal of 3 August 1811:

JAMES BELCHER—This once celebrated pugilist, and a formidable champion of England, died yesterday, at his house, the Coach and Horses, Frith-street, Soho, in the 31st year of his age, after a lingering illness, which had reduced him to a mere skeleton. The deceased arrived in London from Bristol, his native place, as a pugilistic star of the first magnitude, when only eighteen years of age.

And we have star being applied to any exceptional person within a decade or so. From Gerald Griffin’s 1829 The Collegians:

On that night Hardress was one of the gayest revellers at his mother’s ball. Anne Chute, who was, beyond all competition, the star of the evening, favoured him with a marked and cordial distinction.

That’s it. A straightforward and simple etymology and metaphor.

Sources:

Ælfric. De temporibus anni. Heinrich Henel, ed. Early English Text Society OS 213. London: Oxford UP, 1942, 12.

Gneuss, Helmut, ed. “Ave maris stella.” Hymnar und Hymnen im Englischen Mittelalter. Tübingen: M. Niemeyer, 1968, 66.1., 349. London, British Library, Cotton MS Julius A.vi, fol. 57v.

Griffin, Gerald. The Collegians, vol. 2 of 3. London: Saunders and Otley, 1829, 103. HathiTrust Digital Archive.

“London, August 1.” Jackson’s Oxford Journal, 3 August 1811, 2. Gale Primary Sources: British Library Newspapers.

Oxford English Dictionary, third edition, June 2016, modified September 2021, s.v. star, n.1.

Rambler, Harry. Bays in Council, or a Picture of a Green-Room. Dublin: 1751, 4–5. Eighteenth Century Collections Online.

“Royal Circus.” The Monthly Mirror. May 1808, 405. NewspaperArchive.com.

Victor, Benjamin. A History of the Theatres of London and Dublin, vol. 1 of 2. London: T. Davies, et al., 1761, 61–62. Eighteenth Century Collections Online.

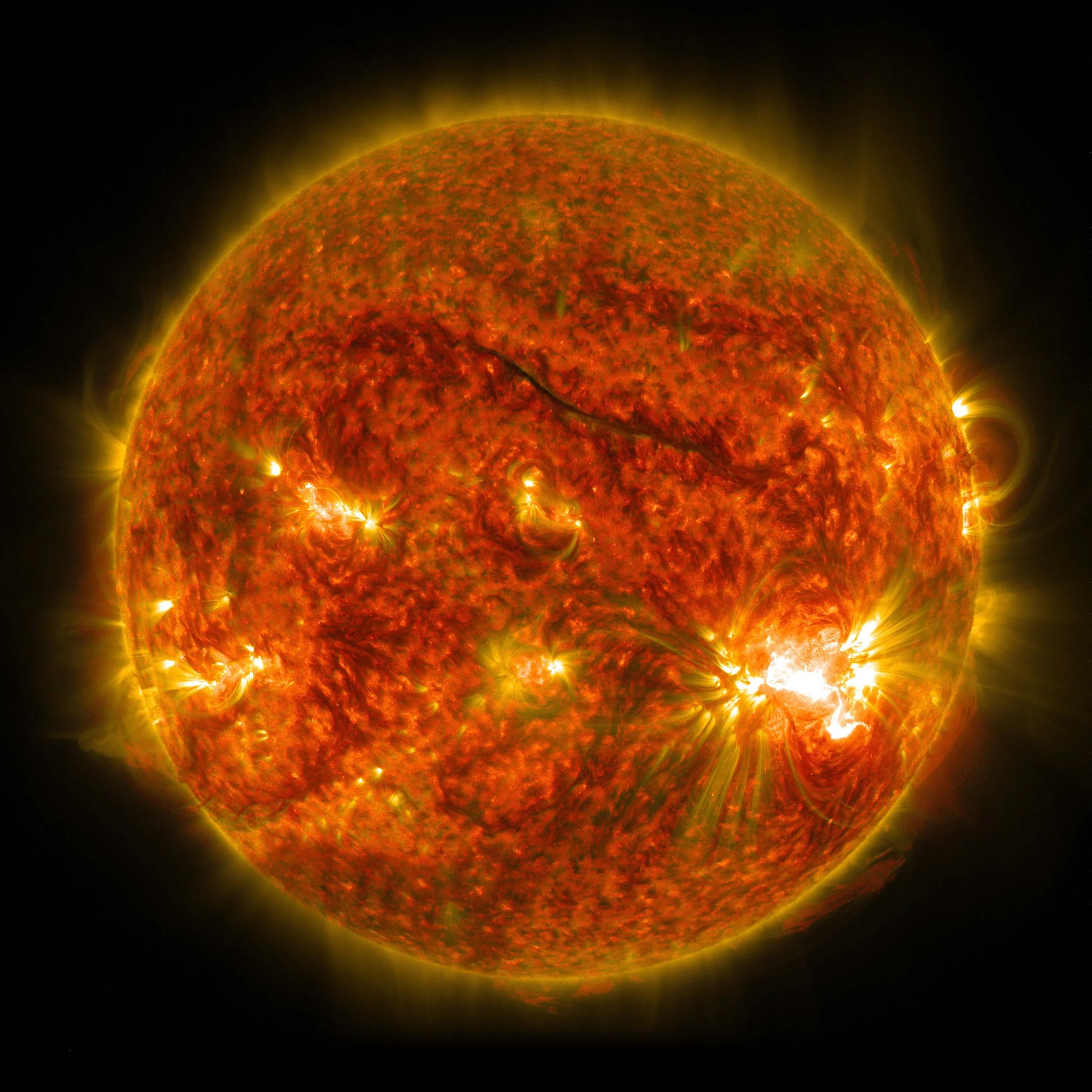

Image credit: NASA Solar Dynamics Observatory, 26 October 2014. Public domain image.