29 December 2021

Spud is a slang term for a potato (cf. potato). The word comes from the name of a digging implement used to uproot them, which in turn is from a term for a short knife or dagger. The ultimate origin of spud is unknown.

The earliest known use of spud, in the sense of a knife, is from c.1440. It appears in the Promptorium parvulorum, an English–Latin dictionary:

Spudd: Cultellus Vilis.

(Spud: inexpensive/cheap knife)

Spud also appears in a play from about the same period, c.1450, The Castle of Perseverance:

Therfore, Mankynde, in this tokenynge,

Wyth spete of spere to thee I spynne,

Goddys lawys to thee I lerne.

Wyth my spud of sorwe swote

I reche to thyne hert rote.

Al thi bale schal torne thee to bote.

Mankynde, go schryve thee yerne.(Therefore, Mankind, in tokening of this,

With the point of a spear I move rapidly to you,

I teach God’s law to you.

With my spud of sweet sorrow

I reach to your heart’s root.

All your torment shall turn you to comfort.

Mankind, go confess quickly.)

But by the early seventeenth century, spud was being used to refer to a digging implement, a sharp blade, mounted on a staff or handle, for cutting through clots of soil and through roots. From Gervase Markham’s 1613 book The English Husbandman:

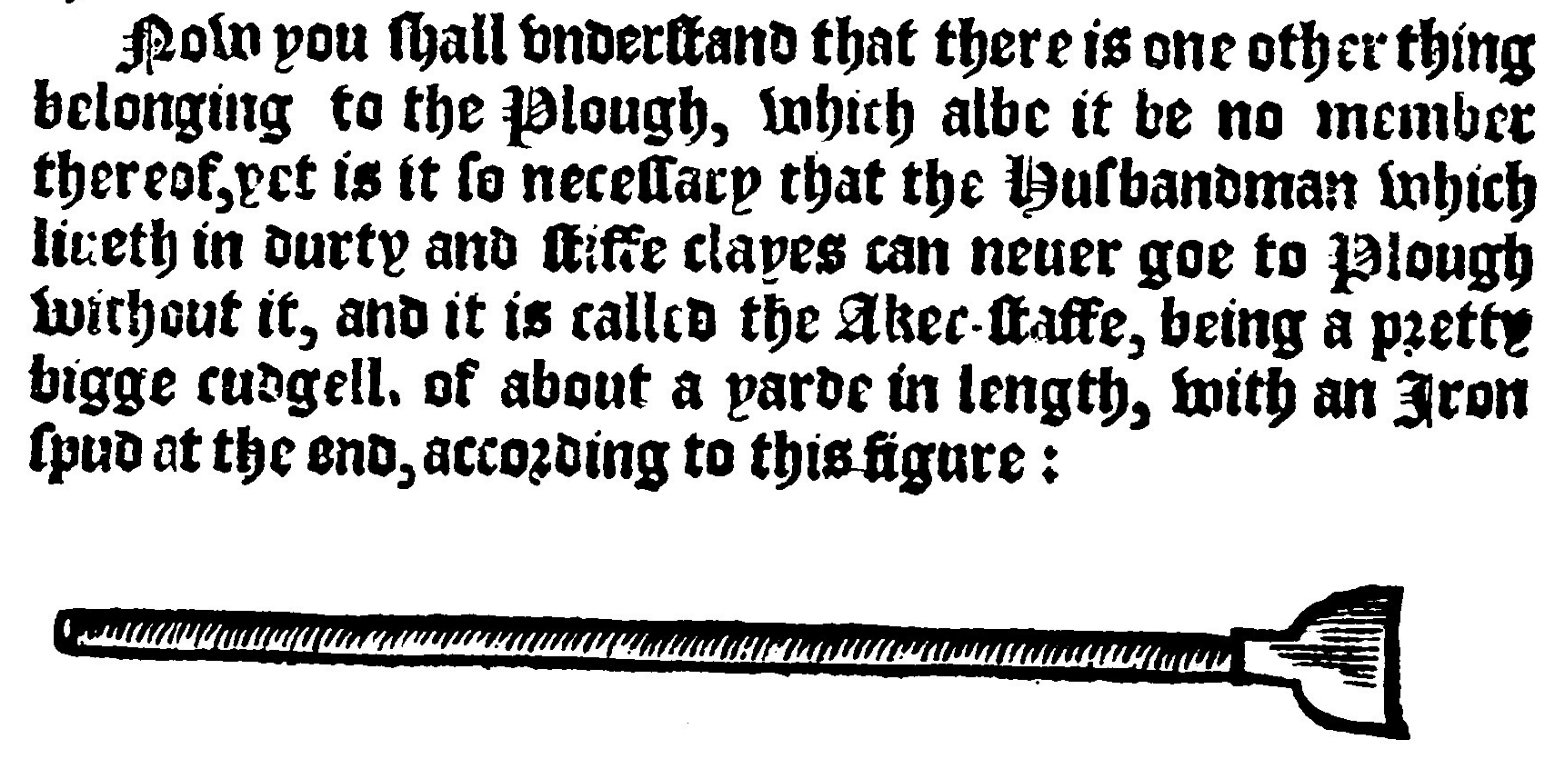

Now you shall vnderstand that there is one other thing belonging to the Plough, which albe it be no member thereof, yet is it so necessary that the Husbandman which liueth in durty and stiffe clayes can neuer goe to Plough without it, and it is called the Aker-staffe, being a pretty bigge cudgell, of about a yarde in length, with an Iron spud at the end, according to this figure:

Spuds were also used to dig up root vegetables, like potatoes. And by the mid nineteenth century, the word was being used to refer to potatoes themselves, an example of the form of semantic change known as metonymy. We can see this in Edward Wakefield’s 1845 Adventure in New Zealand:

Then every article of trade with the natives has its slang term,—in order that they may converse with each other respecting a purchase without initiating the native into their calculations. Thus pigs and potatoes were respectively represented by “grunters” and “spuds;” guns, powder, blankets, pipes, and tobacco, by “shooting-sticks, dust, spreaders, steamers,” and “weed;” A chief was called a “nob;” a slave, a “doctor;” a woman, a “heifer;” a girl, a “titter;” and a child, a “squeaker.”

Sources:

The Castle of Perseverance, David Klausner, ed. Kalamazoo, Michigan: Medieval Institute Publications, 2010, lines 1395–1402. Washington, D.C., Folger Shakespeare Library, MS V.a.354 (5031).

Green’s Dictionary of Slang, 2021, s.v. spud, n.3.

Markham, Gervase. The English Husbandman. London: Thomas Snodham for John Browne, 1613, sig. C1-r. Early English Text Society (EEBO).

Middle English Dictionary, 2019, s.v. spud(de, n.

Oxford English Dictionary, second edition, 1989, s.v. spud, n.

Promptorium parvulorum. Mayhew, Anthony Lawson., ed. Early English Text Society 102. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner, 1908, 430. London, British Library, MS Harley 221. HathiTrust Digital Archive.

Wakefield, Edward Jerningham. Adventure in New Zealand, vol. 1 of 2. London: John Murray, 1845, 319. HathiTrust Digital Archive.

Image credit: Markham’s 1613 The English Husbandman, sig. C1-r. Early English Text Society (EEBO).