31 January 2021

Hocus pocus is a traditional utterance of stage magicians upon performing a trick. It’s part of their patter to distract the audience to prevent them from noticing the sleight-of-hand trick being performing. It’s pseudo-Latin, just nonsense syllables. Its origin is in the early years of the seventeenth century and the court of King James I of England where Hocus Pocus was the stage name of William Vincent, one of the king’s jugglers and magicians (with a side-job as a grifter and swindler).

The phrase hocus pocus appears as early as 1621 in Ben Jonson’s Masque of Augures, in which a character describes a masque within the masque as:

O Sir, all de better, vor an Antick-masque, de more absurd it be, and vrom de purpose, it be euer all de better. If it goe from de nature of de ting, it is de more art, for dere is Art, and dere is Nature; you shall see. Hochos-pochos. Fabros Palabros.

The earliest known mention of the magician is by Anglican priest John Gee in a 1624 anti-Catholic tract. The “they” in the passage is a reference to Jesuits:

Another matter more troubled my curiositie, where and of what Master they learned these trickes of legerdemaine. I alwayes thought they had their rudiments from some iugling Hocas Pocas in a quart pot.

The next year, an account from 18 November 1625 regarding an allegation of fraud identifies Vincent as Hocus Pocus:

William Vincent, alias Hocus Spocus, of London, the Kinge's Majestie's servant, to use his faculty of feales[?] &c, saith he was in company with the said Francis Lane and playd at [ ] for vjd., and soe till Hocus Spocus lost iijs. to Francis Lane, and said he would be halves with him, and would have had him fourth of the roome at Spencer's house into a private place.

Vincent was quite famous in his day. Playwright Ben Jonson mentions him in his 1631 play The Staple of News:

That was the old way, Gossip, when Iniquity came in like Hokos Pokos, in a Iuglers ierkin, with false skirts, like the Knaue of Clubs! but now they are attir'd like men and women o' the time, the Vices, male and female!

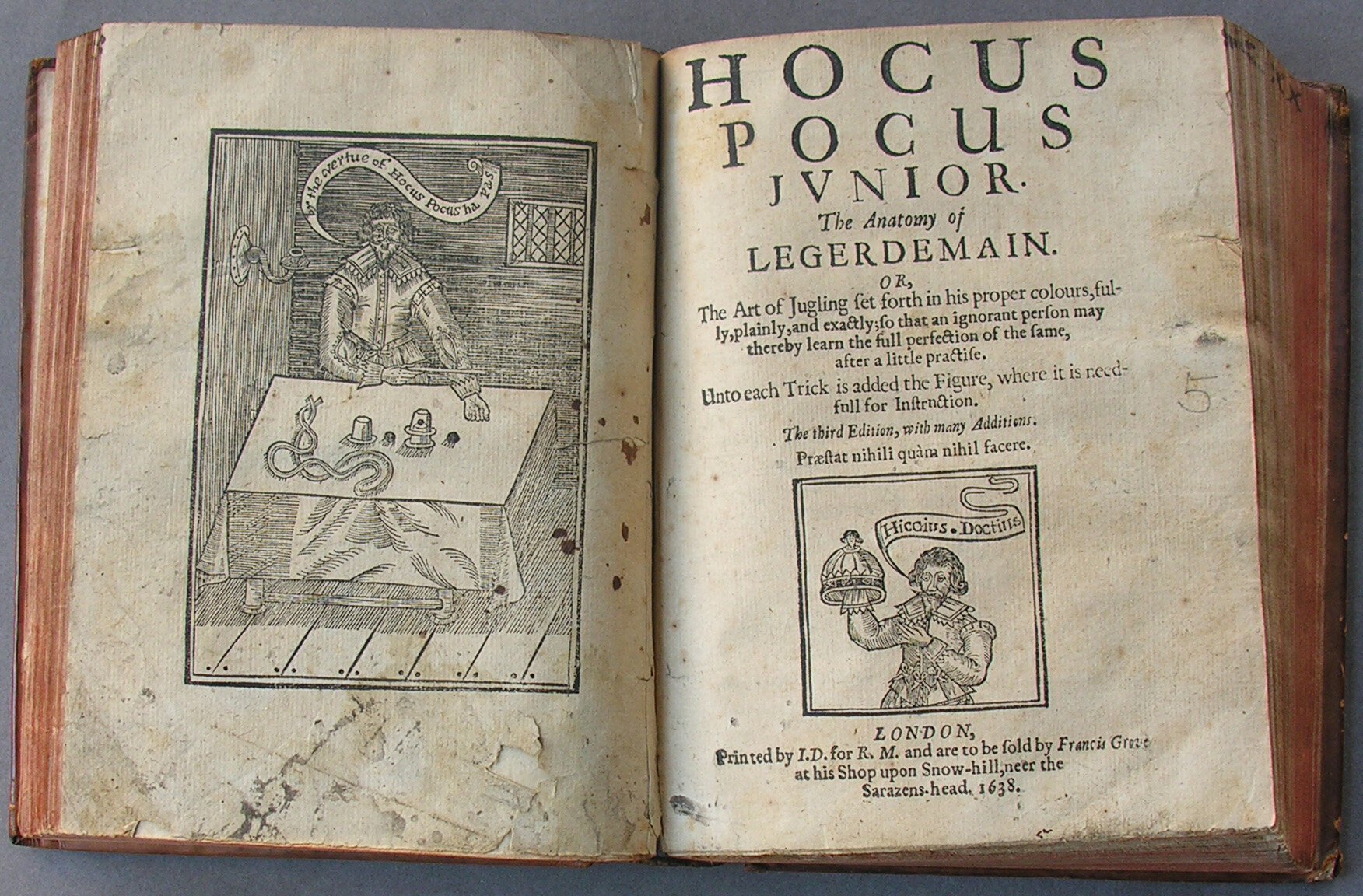

A book of magic tricks titled Hocus Pocus Junior was published in 1634 and went through several editions. The frontispiece of the book, seen here, shows a magician uttering the words hocus pocus as part of an incantation. Scholar of theater Philip Butterworth has argued that Vincent was the author of the book, but the evidence of authorship Butterworth presents is not definitive. In any case, the title is clearly a reference to Vincent, with the book being junior to the man’s senior.

And a few years before that, Thomas Randolph includes this bit of dialogue in his 1632 play The Jealous Lovers. The play was performed for King Charles I, so it would seem that by this date the magician’s patter of hocus pocus was well known, at least among the court:

I think Cupid be turn'd jugler. Here's nothing but Hocas pocas, Praestò be gon, Come again Jack; and such feats of activitie.

And several decades later, physician Thomas Ady gives a fuller account of Vincent’s patter in his 1655 book A Candle in the Dark, an attempt to disprove there is such a thing as witchcraft. The book was used, unsuccessfully, by the defense during the Salem Witch Trials of 1692–93. The mention of hocus pocus comes in a passage discussing different types of magic

The first is profitably seen in our common Juglers, that go up and down to play their Tricks in Fayrs and Markets, I will speak of one man more excelling in that craft than others, that went about in King Iames his time, and long since, who called himself, The Kings Majesties most excellent Hocus Pocus, and so was he called, because that at the playing of every Trick, he used to say, Hocus pocus, tontus talontus, vade celeriter jubeo, a dark composure of words, to blinde the eyes of the beholders, to make his Trick pass the more currantly without discovery, because when the eye and the ear of the beholder are both earnestly busied, the Trick is not so easily discovered, nor the Imposture discerned.

The words hocus pocus, tontus talontus are nonsense, but vade celeriter jubeo is I command you go quickly.

It is sometimes said that hocus pocus is a corruption of the Latin mass in particular the sentence, accipite, et manducate ex hoc omnes: hoc est enim corpus meum (take and eat, all of you, for this is my body). This is unlikely. While it’s certainly possible that hoc est corpus could be misheard as hocus pocus by someone who does not know Latin, the intervening enim militates against this, and the rest of the patter as given by Ady doesn’t match the words in the mass either.

This particular idea got its start, or at least was popularized, by Archbishop of Canterbury John Tillotson, who in 1684 penned an anti-Catholic tract suggesting the magic phrase was a mockery of the Catholic doctrine of transubstantiation. Presumably by this date, memory of Vincent and his stage name had faded from popular memory:

And in all probability those common jugling words of hocus pocus are nothing else but a corruption of hoc est corpus, by way of ridiculous imitation of the Priests of the Church of Rome in their trick of Transubstantiation. Into such contempt by this foolish Doctrine and pretended Miracle of theirs have they brought the most sacred and venerable Mystery of our Religion.

So, that’s it. Hocus pocus comes from the stage name of the most famous magician you’ve never heard of.

Sources:

Ady, Thomas. A Candle in the Dark. London: Robert Ibbitson, 1655, 29. Early English Books Online (EEBO).

Butterworth, Philip. “Hocus Pocus Junior: Further Confirmation of its Author.” Theatre Notebook, 69.3, 2014, 130–35.

Gee, John. New Shreds of the Old Snare. London: J. Dawson for Robert Mylbourne, 1624, 21. Early English Books Online (EEBO).

Guilding, John Melville, ed. Reading Records: Diary of the Corporation, vol. 2 of 4.. London: James Parker, 1895, 264. HathiTrust Digital Archive.

Jonson, Ben. The Masque of Augeres. London: 1621, sig. B.r. Early English Books Online (EEBO).

———. The Staple of News (1631). In The Works of Benjamin Jonson, vol. 2 of 3. London: Richard Meighen, 1640, second intermeane after the act 2, 35. Early English Books Online (EEBO).

Oxford English Dictionary, second edition, 1989, s.v. hocus-pocus, n., adj. and adv.

Randolph, Thomas. The Jealous Lovers. Cambridge: Thomas and John Buck, 1632, 2.5, 25. Early English Books Online (EEBO).

Tillotson, John. A Discourse Against Transubstantiation. London: M. Flesher for Brabazon Aylmer, 1684, 34. Early English Books Online (EEBO).

Image credit: St. John’s College, Cambridge. Public domain in the United States as a mechanical reproduction of a work that was produced before 1925.