As in past years, I’ve come up with a list of words of the year (WOTY). I do things a bit differently from other sites in that I don’t try to select one term to represent the entire year. Instead, I select twelve terms, one for each month.

During the year as each month passed, I selected one word or phrase that was linguistically interesting, prominent in public discourse, or representative of major events of that month. Other such lists that are compiled at year’s end often exhibit a bias toward terms that are in vogue in November or December, and my hope is that a monthly list will highlight words that were significant earlier in the year and give a more comprehensive retrospective of the planet’s entire circuit around the sun. I also don’t publish the list until late in December; selections of words of the year that are made in November (or even earlier!), as some of them are, make no sense to me. You cannot legitimately select a word to represent a year when you’ve still got over a month or even two left to go.

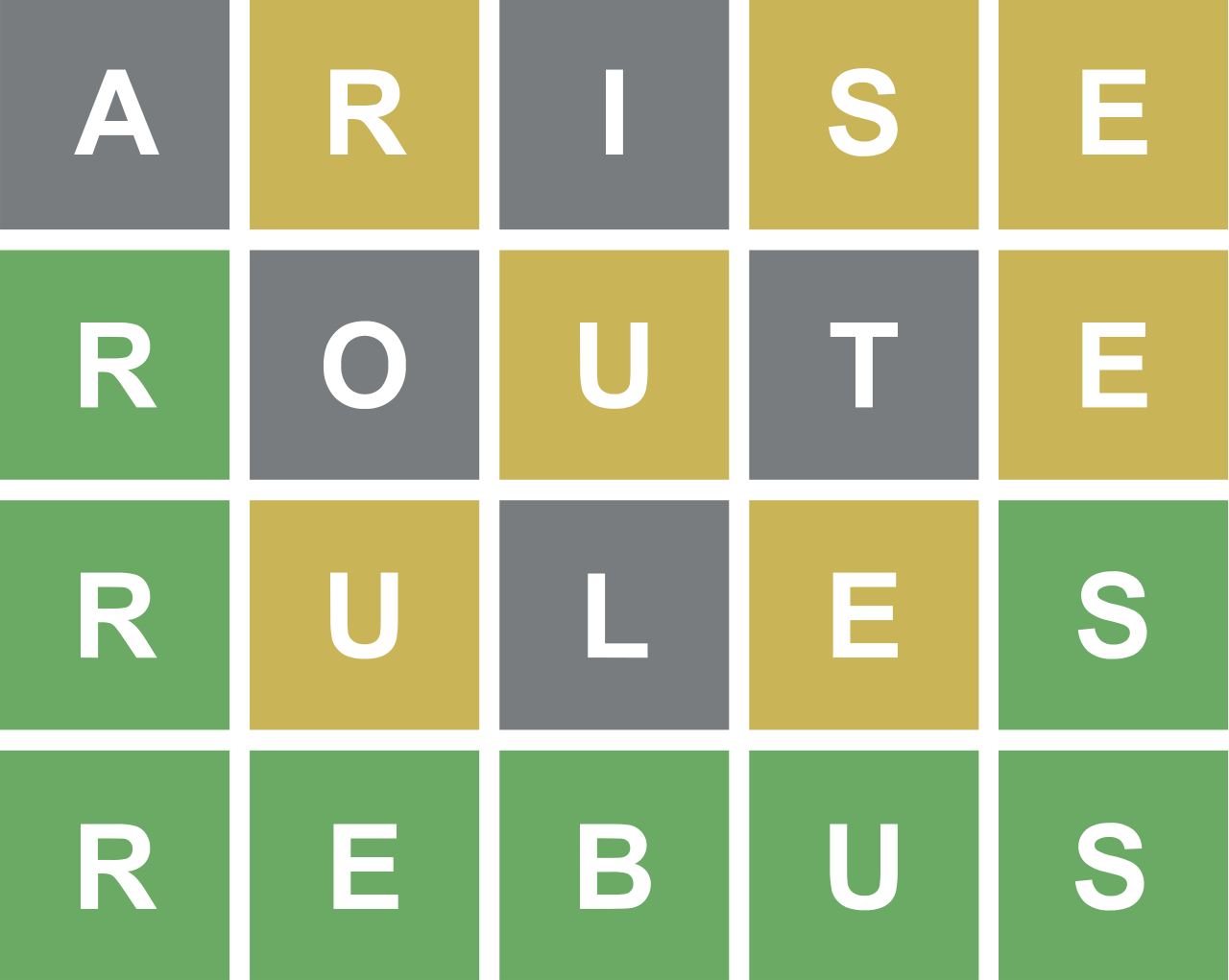

January: Wordle

Invented by Josh Wardle in October 2021, the web-based word game Wordle became a sensation in January 2022. Rights to publish the game were subsequently purchased by the New York Times.

February: convoy

The so-called freedom convoy (convoi de la liberté) protest began in Canada in January 2022 and reached its height in February. Beginning as a protest of vaccine mandates for those crossing the US-Canadian border, the protest quickly degenerated into a generic anti-government protest and a hodgepodge of racist and alt-right demands. The protest succeeded in shutting down the Parliament Hill area of Ottawa for several days, before being peacefully quashed by police. Attempts at similar protests elsewhere in Canada and in the US fizzled out.

March: Z

Russia invaded Ukraine in February, with the war continuing throughout the year. Many Russian vehicles involved in the invasion had Latin letters painted on them, Z, V, and O, which are believed to be designations of different Russian army groups. By March, the Z-symbol had become a marker of support for the invasion and pro-Putin politics in general.

April: quiet quitting

Quiet quitting is the trend of doing the minimum required at one’s job in order to improve one’s work-life balance and in recognition that corporations have traditionally taken advantage of workers’ desire to please their bosses. The trend is part of the pro-labor sentiment that followed in the wake of the pandemic. The first known use of the term was in a March 2022 TikTok video by career coach Bryan Creely.

May: monkeypox

An outbreak of monkeypox, predominantly but not exclusively infecting gay and bisexual men, occurred in the United Kingdom in May and rapidly spread globally. It was the first major outbreak of the disease outside of Africa. Following on the heels of the coronavirus pandemic, the outbreak was just one more blow to an already tired world.

Monkeypox is an orthopox virus related to chickenpox and smallpox and generally falling between those two diseases in severity. It is primarily a zoonotic disease, but outbreaks among humans have been increasing since smallpox vaccinations, which also confer a degree of immunity to the related monkeypox, have ceased. The 2022 outbreak was largely under control and fading by year’s end.

June: inflation

The lifting of pandemic restrictions and the consequent release of pent-up demand compounded by limited supply resulted in the first major bout of inflation the United States and the United Kingdom had seen in decades. Much discussed in the media and widely thought to presage a major defeat for the Democrats in the November 2022 mid-term election, it did not have that effect. While inflicting economic hardship on many, the inflation, which was waning by year’s end, did not seem to have a major effect on politics.

July: JWST

In July, NASA, the European Space Agency, and the Canadian Space Agency released the first images from the newly launched James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), the long-awaited replacement for the Hubble telescope. The images were stunning and heralded major advances in astronomy and cosmology that will be coming in the next decade.

But while the JWST’s science is unassailable, its name has been controversial. James Webb was the Apollo-era administrator of NASA, and the telescope’s name was chosen unilaterally in 2002 by then-NASA administrator Sean O’Keefe. In accordance with NASA policy, scientific space missions are supposed to be named via a public process, typically for astronomers and physicists, and the name is not officially given until after launch (so as not to offend family members in case of launch failure). In contrast, the JWST was named via a secret process, Webb was not a scientist but a Cold War bureaucrat, and the telescope was named two decades prior to launch. Additionally, legitimate questions have been raised about Webb’s role in discriminating against LGBTQ government employees when he was an administrator in the State Department and at NASA. Webb’s leadership during the Apollo program was certainly noteworthy, but there are many who think that a more apt namesake should have been found.

August: raid

In August, the US Federal Bureau of Investigation executed a search warrant on Donald Trump’s Mar-a-Lago compound in Florida, finding a large number of classified and unclassified government documents that had been illegally removed from the White House before his leaving office in 2021. The unprecedented search of a former president’s home was labeled a raid by many news outlets, and debate over whether that term was appropriate or not ensued.

September: morality police

On 13 September 2022, Mahsa Amini, a 22-year-old Kurdish-Iranian woman was arrested by the Iranian Guidance Patrol (gašt-e eršād), commonly known as the morality police, for improper wearing of the hijab. Three days later she died from severe blows to the head suffered during her custody. Her death sparked continuing protests inside and outside Iran, the largest and most sustained domestic protests against the Iranian government since the 1979 revolution. In December, the government allegedly disbanded the morality police, but the announcement of the force’s dissolution has been widely seen as a public relations ploy and is thought to be in name only.

October: Carolean

With the death of Queen Elizabeth II in September, the second Elizabethan era ended. Elizabeth had been the longest reigning British monarch and the longest reigning female monarch anywhere. The accession of her son Charles III to the throne caused some to question what the new era would be labeled, and in October it became clear that the term would be Carolean. Given Charles’s age, the Carolean era will undoubtedly be considerably shorter that the Elizabethan era of his mother.

November: Mastodon

Elon Musk completed his acquisition of the Twitter social media platform on 27 October 2022. Within days Musk threw the social media platform into disarray, driving away employees, users, and advertisers with his unbanning of fascist and racist users and unhinged attempts to suppress criticism of him and his actions. The Mastodon platform has been widely touted as a haven for disaffected Twitter users. Whether or not Mastodon will succeed in becoming the Twitter replacement or if another platform will claim that honor is not yet known, but the name Mastodon represents the seismic shift and petty grievances that Musk and his actions have engendered in the social media landscape.

December: GOAT

In December, the Argentinian football team, led by 35-year-old striker Lionel Messi, won the 2022 World Cup. Messi, who has been widely hailed as the Greatest of All Time (GOAT), finally won the World Cup that that had been eluding him. With other contenders for the GOAT title, like fellow South Americans Pelé, Ronaldo, and Maradona, one may contest the use of the superlative in Messi’s case, but there is no doubt that Messi should be listed among those other legends of the game. The 2022 World Cup was controversial due to FIFA’s continuing corruption and host-nation Qatar’s human rights violations, but Messi’s and the Argentinian team’s well-deserved victory was a sweet ending to an otherwise turbulent tournament and year.

Image credits: 2022: Vikayaskina, 2021. Wordle: Josh Wardle (game), public domain image; convoy: Véronic Gagnon, 2022, licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license; Z: Border Guard Service of Ukraine, 2022, licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license; quiet quitting: Mohamed Hassan, 2021, licensed under the Pixabay terms of service; monkeypox: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), 2022, public domain image; inflation: J.J. Liu, 2022, public domain image; JWST: NASA/ESA/CSA, 2022, public domain image; raid: US Department of Justice, 2022, public domain image; morality police: VaneMG (mural) and Loco Steve (photo), photo licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 license; Carolean: Royal Mint, 2022, fair use (editorial) of a copyrighted image; Mastodon: Mastodon, 2017, licensed under a GNU Affero General Public License for non-trademark use; GOAT: Hossein Zohrevand, Tasnim News Agency, 2022, licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.